Abstract

Substantial terrestrial gas emissions, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), are associated with active volcanoes and hydrothermal systems. However, while fundamental for the prediction of future activity, it remains difficult so far to determine the depth of the gas sources. Here we show how the combined measurement of CO2 and radon-222 fluxes at the surface constrains the depth of degassing at two hydrothermal systems in geodynamically active contexts: Furnas Lake Fumarolic Field (FLFF, Azores, Portugal) with mantellic and volcano-magmatic CO2, and Syabru-Bensi Hydrothermal System (SBHS, Central Nepal) with metamorphic CO2. At both sites, radon fluxes reach exceptionally high values (> 10 Bq m−2 s−1) systematically associated with large CO2 fluxes (> 10 kg m−2 day−1). The significant radon‒CO2 fluxes correlation is well reproduced by an advective–diffusive model of radon transport, constrained by a thorough characterisation of radon sources. Estimates of degassing depth, 2580 ± 180 m at FLFF and 380 ± 20 m at SBHS, are compatible with known structures of both systems. Our approach demonstrates that radon‒CO2 coupling is a powerful tool to ascertain gas sources and monitor active sites. The exceptionally high radon discharge from FLFF during quiescence (≈ 9 GBq day−1) suggests significant radon output from volcanoes worldwide, potentially affecting atmosphere ionisation and climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since decades, the tenuous relation between Earth’s deformation, earthquakes, and carbon dioxide (CO2) release has fostered broad interest in the geoscience’s community1,2. Significant CO2 emissions have been commonly reported at the plate boundaries in a variety of seismotectonic regimes: extension (rifting)3, reverse fault4, strike-slip fault5, subduction6, triple junction7, and collision8. To appreciate the potential coupling between geodynamics and CO2, we need to better understand CO2 sources and transport mechanisms. Besides biological sources, the released geogenic CO2 generally has either a volcano-magmatic, a mantellic or a metamorphic source, or a mixing of these. The number of available data-sets on CO2 release has increased9, and it appears timely to evaluate the available results against each other. Comparing CO2-emitting sites in different active tectonic settings may help diagnose the involved gas transport mechanisms and constrain the depth of degassing (i.e., gas source depth). Both are delicate questions at all sites, but appear fundamental for long-term monitoring, prediction, and health risk assessment of the population. For this purpose, coupling CO2 measurement with that of a trace gas, such as helium, mercury or radon, may reveal of utmost value.

Radon-222, a noble, alpha-emitter radioactive gas with half-life of 3.8 days, is produced in the upper crust by alpha-decay of the solid radium-226. Tagged as a tracer of fluid transport at several active faults and hydrothermal systems worldwide, it was found sensitive to deformation and earthquakes, both in the field10,11 and laboratory12,13, although many claimed precursory signals remain controversial14. To migrate from its source to the surface before decaying, radon needs to be transported by a carrier fluid having a sufficient velocity, such as CO2, at high-permeability geosystems. Indeed, the use of radon to constrain gas transport and source has been pioneered at a few CO2-emitting sites. For example, at Santorini volcano (Greece), carbon isotopic composition was compared with radon concentration, but without accounting for heterogeneity of the layers crossed by the fluid mixture15. At Mt. Etna volcano (Italy), radon transport was modelled through geological layers, but without accounting for production terms within the layers16. At Pantelleria Island (Italy) and Nisyros volcano (Greece), 222Rn/220Rn concentration ratios and few radon source term values in soils and rocks were used, but without radon transport modelling17,18. To infer constraints on gas source and transport mechanisms by coupling CO2 and radon measurements, a radon transport model, together with a thorough characterisation of radon sources, is necessary to interpret the data.

Here, we apply a combined approach of coupling the measurements of CO2 flux and radon flux from the ground surface to constrain the depth of degassing at two geodynamically active sites with different CO2 sources: Furnas Lake Fumarolic Field (FLFF), São Miguel Island, Azores archipelago, Portugal with mantellic and volcano-magmatic CO2 sources, and Syabru-Bensi Hydrothermal System (SBHS) in the Himalayas of Central Nepal with a metamorphic CO2 source. We show that the combination of radon flux, CO2 flux, radon sources, and CO2 sources, interpreted using a common simplified multiphase radon transport model, constrains the depth of CO2 degassing at both volcanic (FLFF) and active fault sites (SBHS), and allows quantifying deep-originated gas fluxes to the atmosphere.

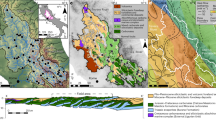

The Azores archipelago, formed by nine volcanic islands along a WNW-ESE trend, is located in the North Atlantic Ocean at the triple junction of the American, Eurasian, and Nubian tectonic plates. The largest island, São Miguel, comprises three dormant trachytic polygenetic volcanoes (from west to east: Sete Cidades, Fogo, and Furnas)19. Furnas volcano (Fig. 1a), with an age of approximately 100,000 years B.P., is formed by two nested calderas controlled by a NW-SE and NE-SW trending fault system20. The western part of the youngest caldera is filled by a shallow (≤ 15 m depth) lake. Several eruptive styles occurred at Furnas volcano, from effusive to caldera-forming explosive events, with a total of 10 intra-caldera eruptions in the last 5000 years21. Since the fifteenth century, two major eruptions have occurred: one event in 1439‒1443 and one deadly subplinian event in 1630. The erupted products were mainly pumices, ashes and lapilli, surges and trachytic lava domes20.

(a) Geological map showing the location of the Furnas Lake Fumarolic Field (FLFF) in mantellic and volcano-magmatic context (Azores, Portugal). The insets show the location of the Azores and of the Furnas Volcano on the São Miguel Island. (b) Geological map showing the location of the Syabru-Bensi Hydrothermal System (SBHS) in metamorphic and active tectonic context (Central Nepal). The inset shows the location in the Nepal map.

The current volcanic activity takes the form of secondary manifestations, such as boiling fumaroles, thermal and cold CO2-rich springs, and CO2 diffuse degassing structures (DDS). One of the main degassing areas (Fig. 1a) is Furnas Lake Fumarolic Field (FLFF) located north of Furnas Lake22. Gas released is dominated by water steam and CO2, with detectable traces of H2S, H2, N2, CH4, Ar, He, and CO22. According to the recently published conceptual model, the released gases come from the final cooling of a trachytic reservoir located around 3‒4 km depth23, percolate through the fracture network, dissolve in shallow meteoric aquifers with vapour/liquid equilibrium temperature around 270 °C in Furnas Lake area, degas and then percolate to the surface22,24. This is consistent with various geophysical soundings performed at FLFF, which showed P-wave low velocity zone at 6 km depth25, low density magma bodies at 4‒5 km depth26, and conductive zones at 500 m and 100 m depth27 dipping below the lake28. Chemistry and isotopic composition of thermal waters and fumaroles at FLFF7,22,29,30 suggest mantellic and volcano-magmatic CO2 (δ13C = − 4.5 ± 0.2 ‰; n = 3) and a mixing of mantellic and crustal components for helium (R/Ra = 5.25 ± 0.02; n = 3).

The Azores climate is oceanic temperate, with a mean annual temperature of 17 °C (minimum of 14 °C in January and maximum of 25 °C in August). The mean annual precipitation of 1930 mm year−1 is marked by a strong seasonality between a rainy season from October to March (75% of annual precipitation) and a dry season in summer31. At FLFF, CO2 is released by fumaroles, DDS, and thermal springs. Several CO2 flux studies7,32 have been carried out at the four main CO2 emitting areas of Furnas volcano (FLFF, Furnas Village, Ribeira dos Tambores, and Ribeira Quente Village). Recent total estimated gaseous CO2 discharge from FLFF33 amounts to 35 t day−1, among which DDS represent33,34 6.0 ± 0.2 t day−1 and 19.8 t day−1, respectively over 4000 m2 and 20,000 m2 surface area. In the FLFF surroundings, a permanent CO2 flux station is operating since 200432,35. Potential radon sources may be associated with 226Ra excess in basaltic lavas36, 226Ra secondary mineralisation within ashes, pumices, lapilli, and altered soil surface, and 226Ra dissolved in thermal waters. Large radon concentrations are reported in the ground (max: 390,000 Bq m−3) and in habitations (max: 13,300 Bq m−3) at Furnas volcano37,38, which, together with CO2, pose substantial health hazard to the population7,39.

The second site considered in this paper is located in the Nepal Himalayas. The Himalayan orogen results from the India–Eurasia collision which started 55 Ma ago. Half of the continent–continent shortening, 2 cm year−1, is accommodated by the large décollement called the Main Himalayan Thrust (MHT)40. In Nepal, the last large earthquake, the 2015 Mw7.9 Gorkha earthquake, claiming > 9000 lives, ruptured the MHT over 150 km41. About 4–5 events of local magnitude ML > 5 occur per year, concentrated at 10–25 km depth, at the foot of the Himalayan topographic rise42. This area, the Main Central Thrust (MCT) zone43, is a 2- to-10-km-width shear zone that separates high-grade meta-crystalline rocks from the Greater Himalaya to the north from low-grade meta-sedimentary rocks from the Lesser Himalaya to the south.

Along the whole Himalayas, the MCT zone comprises numerous hydrothermal systems characterised by thermal and cold CO2-rich springs44,45, ‘tectonic’ fumaroles, and CO2 DDS46, with significant CO2 emissions concentrated along a 110-km-long segment in Central Nepal47. The upper Trisuli valley (Fig. 1b), located 60 km north to Kathmandu, encompasses several CO2-emitting hydrothermal sites in the vicinity of the MCT zone and shows the largest Himalayan CO2 release reported so far (> 15 ± 3 t day−1)47,48. This valley also reported significant post-seismic hydrothermal changes following the Gorkha earthquake8. One of these sites, Syabru-Bensi Hydrothermal System (SBHS) (Fig. 1b), is located 3.5 km south to MCT within the Lesser Himalayan rocks comprising mainly mica-schist, quartzite, marble, graphitic schist, and augen gneiss49,50,51. Gas released is dominated by CO2, with water steam and large H2S content (340 ppm). According to the most recent conceptual model8, CO2-rich gas comes from a deep source at > 5 km depth, percolates through fracture networks in the MCT zone, forms gas reservoirs and mixes with meteoric water, degasses at a depth of 100 m or more at 70 °C ≤ T ≤ 120 °C (vapour/liquid equilibrium temperature), and then crosses near-surface aquifers before reaching the surface. This appears consistent with geophysical soundings carried out at SBHS and in the valley which showed a highly conductive and low P-wave velocity zone at ≈ 10 km depth52, conductive zones at 10‒30 m depth and shallow altered fractured conduits for gas below the SBHS53, and self-potential anomalies at the surface53,54. Chemistry and isotopic composition of thermal waters and DDS at SBHS8,44,45,54 suggest CO2 production by metamorphic decarbonation at > 5 km depth, a dominating crustal carbon component of the gaseous CO2 (δ13C = − 0.75 ± 0.01‰; n = 27), and radiogenic helium (R/Ra ≤ 0.05; n = 2).

Circumvented respectively to the west, north, and east by Ganesh, Tibet, and Langtang ranges, SBHS benefits from a rain shadow effect of Gosainkunda range to the southeast. The mean annual precipitation varies from 1100 to 1800 mm year−1. Monsoon occurs from June to September (80% of annual precipitation) and dry season from December to February55. The mean annual air temperature is 19 °C, with minimum of 0 °C in January and maximum of 28 °C in June. At SBHS, CO2 is released by fumaroles, DDS, and thermal springs. Several CO2 flux studies8,46,47,54,56 have been carried out at the five main CO2-emitting areas of SBHS. Total estimated gaseous CO2 discharge from SBHS8,47,54 amounts to 8 t day−1, among which 3.8 ± 0.4 t day−1 corresponds to DDS of gas zones 1 and 2 over a surface area of 11,000 m2. At this site, several radon measurement campaigns reported large radon fluxes at the surface (max: 38,500 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1) and radon concentrations in the ground (max: 57,700 Bq m−3)8,46,54,57. Radon sources have also been investigated in the thermal and cold waters, the soil, and the surrounding rock layers50,54,58. These high CO2 and radon releases also pose a health hazard to the local population and animals54,57.

Results

Radon and CO2 fluxes at Furnas Fumarolic Field

Radon and CO2 fluxes were measured in June 2016 at the surface using the accumulation chamber method (see “Methods” section; Supp. Fig. S1) around the main boiling fumaroles and near the lakeshore. A total of 169 radon and 371 CO2 flux measurements were performed at 136 and 335 locations (Table 1), respectively, over a surface area of 48,000 m2. Fluxes were measured along several profiles every 2 to 5 m (Supp. Fig. S2).

Mean radon flux values range over five orders of magnitude from 1.3 to 40,000 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1 (Fig. 2a). The largest radon fluxes (> 10,000 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1) are found in the fumarolic area. Such huge values are commonly reported on uranium mill tailings (see review54). The overall arithmetic (geometric) mean for radon fluxes amounts to 4300 ± 600 (560 ± 10) × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1, which is more than three times larger than the few reported mean radon flux values obtained at volcanic sites worldwide (see review54). The distribution of radon flux values is bimodal (Fig. 2a), with populations A (55%) and B (45%) separated by a threshold value of 870 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1 using normal probability partitioning59 (Table 1); the median (720 ± 20 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1) is larger than the mean. Mean CO2 flux values range over five orders of magnitude from 8.1 to 27,000 g m−2 day−1 (Fig. 2c), with the largest values (> 1000 g m−2 day−1) also found in the fumarolic area. The overall arithmetic (geometric) mean for CO2 fluxes amounts to 1200 ± 200 (139 ± 1) g m−2 day−1, compatible with past measurement campaigns7,33,34. The distribution of CO2 flux values is bimodal, with populations A (81%) and B (19%) separated by a threshold value of 720 g m−2 day−1 (Table 1); the median (83.3 ± 0.2 g m−2 day−1) is smaller than the mean.

Distributions of radon and CO2 fluxes measured at both sites (in logarithmic scale): on the left, radon flux at (a) FLFF and (b) SBHS; on the right, CO2 flux at (c) FLFF and (d) SBHS. Geometric mean of each distribution is represented as a vertical dashed black line and the cumulated distribution as a solid black curve (scale on the right-hand side).

Based on the whole flux data-set and using sequential Gaussian simulations (see “Methods” section), maps of radon and CO2 fluxes are obtained at FLFF (Fig. 3). The largest radon fluxes are concentrated in the fumarolic area, near the parking, and on the eastern part, while the lowest are found in the western lakeshore and between the fumarolic area and the parking (Fig. 3a). Significant spatial variations of radon flux are found within the fumarolic area over an area of 80 × 100 m2 (inset of Fig. 3a), with difference of several orders of magnitude within few metres only. On the eastern part, large radon fluxes appear isolated. The largest CO2 fluxes are also concentrated in the fumarolic area, near the parking and on the eastern part, while the lowest are found in the western lakeshore and between the fumarolic area and the parking (Fig. 3b). Significant spatial variations of CO2 flux, larger than for radon fluxes, are found within the fumarolic area (inset of Fig. 3b), with difference of several orders of magnitude within few metres only. On the eastern and western parts and near the parking, large CO2 fluxes reflect areas with a higher mean CO2 flux. The surface area of large CO2 flux is larger than that of large radon flux.

Interpolated (a) radon and (b) CO2 flux maps of FLFF. For each flux map, the colour scale is shown on the bottom right. In (a,b), the inset is an enlargement of the fumarolic area. The map is projected following the UTM coordinate system. The map was built using sGs method with a cell size of 3 m2 (see “Methods” section).

Based on our data-set, past CO2 flux campaigns7, and the literature, mean background fluxes are estimated as 22 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1 for radon and 25 g m−2 day−1 for CO2. The surface areas of radon and CO2 fluxes above background yield 43,700 and 45,200 m2, respectively (about 97% of the investigated surface area). Exceptionally large radon (> 1000 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1) and CO2 fluxes (> 1000 g m−2 day−1) occupy a surface area of 23,900 m2 (54%) and 3600 m2 (8%), respectively. The total estimated radon discharge amounts to 9300 ± 1600 MBq day−1 (108,000 ± 19,000 Bq s−1). To date, this huge estimate is the first obtained at a volcanic hydrothermal system. The total estimated CO2 discharge amounts to 19.1 ± 5.3 t day−1 (5.0 ± 1.4 mol s−1). This value, consistent with reported CO2 discharges obtained during past campaigns7,34, is similar to other volcanic sites worldwide47.

Radon and CO2 fluxes at Syabru–Bensi hydrothermal system

Radon and CO2 fluxes were regularly measured from 2009 to 2020 at the surface using the accumulation chamber method (see “Methods” section; Supp. Fig. S1) around the tectonic fumaroles and non-vegetated areas, 20 m above the main hot springs (gas zones 1‒2). A total of 418 radon and 777 CO2 flux measurements were performed at 250 and 399 locations (Table 1), respectively, over a surface area of 3000 m2. Fluxes were measured along several profiles every 1 to 2 m (Supp. Fig. S3).

Mean radon flux values range over five orders of magnitude from 1.0 to 20,000 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1 (Fig. 2b). The largest radon fluxes (> 10,000 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1) are concentrated near the tectonic fumaroles. The overall arithmetic (geometric) mean for radon fluxes amounts to 1100 ± 100 (234 ± 3) × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1. The distribution of radon flux values is bimodal (Fig. 2b), with populations A (43%) and B (57%) separated by a threshold value of 130 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1 (Table 1); the median (230 ± 10 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1) is similar to the mean. Mean CO2 flux values range over six orders of magnitude from 2.8 to 160,000 g m−2 day−1 (Fig. 2d). The largest CO2 fluxes (> 1000 g m−2 day−1) are also measured in the vicinity of the fumaroles. The overall arithmetic (geometric) mean for CO2 fluxes amounts to 6500 ± 1000 (284 ± 3) g m−2 day−1. The distribution of CO2 flux values bears three modes (Fig. 2d), with populations A (55%), B (34%) and C (11%) separated by threshold values of 260 and 7800 g m−2 day−1, respectively (Table 1); the median (174 ± 1 g m−2 day−1) is smaller than the mean.

Similarly (see “Methods” section), maps of radon and CO2 fluxes are obtained at SBHS (Fig. 4). The largest radon fluxes are concentrated in the vicinity of small recesses at the base of terrace scarps, in non-vegetated areas, and at the foot of the terraces arranged for crops, while the lowest are found in the southern and northern parts of the alluvial and debris fall terrace (Fig. 4a). Here also, metre-scaled variations of radon flux of several orders of magnitude are noticed around recesses and non-vegetated areas over a surface area of 30 × 45 m2 (Fig. 4a). In the western area, large radon fluxes are found in the vicinity of inhabited housings. The largest CO2 fluxes are also concentrated inside and near the recesses, in non-vegetated areas, and at the foot of terraces, while the lowest are found in the southern and northern parts (Fig. 4b). Similarly, significant spatial variations of CO2 flux are found near the recesses and non-vegetated areas (Fig. 4b), with difference of several orders of magnitudes within few metres only. Here also, the surface area of large CO2 flux is larger than that of large radon flux.

Interpolated (a) radon and (b) CO2 flux maps of SBHS. For each flux map, the colour scale is shown on the bottom right. The map is projected following the UTM coordinate system. The map was built using sGs method with a cell size of 1 m2 (see “Methods” section).

Based on the overall data-set, mean background fluxes are estimated as 22 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1 for radon and 10 g m−2 day−1 for CO2. The surface areas of radon and CO2 fluxes above background yield 940 m2 and 3000 m2, respectively (about 99% of the investigated surface area). Exceptionally large radon (> 1000 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1) and CO2 fluxes (> 1000 g m−2 day−1) occupy a surface area of 170 m2 (18%) and 890 m2 (29%), respectively. The total estimated radon discharge amounts to 71 ± 11 MBq day−1 (820 ± 130 Bq s−1). The total estimated CO2 discharge amounts to 6.3 ± 1.6 t day−1 (1.65 ± 0.41 mol s−1), similar to previously published values at this site8,54 and to other mofette sites worldwide47.

Radon sources

At FLFF and SBHS, numerous potential sources of radon were investigated (Table 2). At FLFF, 45 soil and 18 rock samples were analysed for their effective radium-226 concentration (ECRa, or radon source term; see “Methods” section). Soil samples consist mostly of altered surface rich in kaolinite and marcasite29 in the fumarolic area (n = 30), and of pumice volcanic material of the latest explosive eruption35 outside (n = 15). Soil ECRa values range from 2.3 to 21 Bq kg−1, with an arithmetic (geometric) mean of 8.6 ± 0.7 (7.4 ± 0.1) Bq kg−1 (Supp. Fig. S4). This value is consistent with the mean ECRa value for soils60,61 (≈ 7 Bq kg−1; n = 2070). ECRa values for volcanic rocks from samples collected inside and around the Furnas caldera, i.e. altered rock and pumice (lapilli and ash), range from 0.3 to 34 Bq kg−1, with arithmetic (geometric) mean of 6.2 ± 2.0 (3.2 ± 0.1) Bq kg−1 (Supp. Fig. S4), significantly larger than the mean ECRa value for volcanic rocks60 (1.7 ± 0.2 Bq kg−1; n = 349; Supp. Fig. S5a), suggesting a crustal signature.

Radon concentration in ground gas, measured at 86 locations (see “Methods” section), ranges from 179 to 377,000 Bq m−3, with a mean of 33,100 ± 7200 Bq m−3, consistent with reported values37,38 and mean radon concentration in water bubbling (74,000 ± 18,000 Bq m−3). By contrast, radon concentration in the boiling fumarole is low (810 ± 31 Bq m−3). Mean radium-226 and radon concentrations in thermal water (see “Methods” section) are low (means of 63 ± 32 × 10−3 Bq L−1 and 4.1 ± 0.2 Bq L−1, respectively), in the lower range of values for hydrothermal waters62.

At SBHS, 68 soil and 19 rock samples give arithmetic mean (min‒max) ECRa values of 9.2 ± 0.7 (1.0‒43) and 2.5 ± 0.5 (0.13‒7.5) Bq kg−1, respectively (Supp. Fig. S4). Soil consists of debris fall deposit of mica-schist mixed with alluvial soil in the vegetated area, and of hydrothermal soil (“reduktosol” or “mofettic” qualification63) richer in organic matter, clay, and secondary iron oxides54 in the non-vegetated area. The metamorphic rocks are mainly garnet-rich mica-schist, marble, and quartzite. Their ECRa values are relatively similar to the mean ECRa value for metamorphic rocks (5.1 ± 0.4 Bq kg−1; n = 1256; Supp. Fig. S5b). Mean soil ECRa is similar to that obtained at FLFF, but mean rock ECRa is smaller.

Radon concentration in ground gas, measured at six locations, yields mean of 43,000 ± 1800 Bq m−3. Bubbling waters, only reported on the opposite river bank, give smaller radon concentration in water bubbles (mean: 11,300 ± 1600 Bq m−3). Similarly, mean radium-226 and radon concentrations in thermal waters are not exceptional (means of 125 ± 66 × 10−3 Bq L−1 and 15 ± 9 Bq L−1, respectively).

CO2 sources

At FLFF, ground gas CO2 concentration, measured at 89 locations (see “Methods” section), ranges from 0.3 to ≈ 100 vol% (mean: 57 ± 4%), consistent with reported values7,39. Total dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) concentration in thermal waters gives 9.0 ± 0.9 × 10−3 mol L−1. The carbon isotopic composition of CO2, with mean δ13C of − 4.2 ± 0.3‰ for gaseous CO2 and − 4‰ for DIC, confirms the mantellic and volcano-magmatic CO2 sources (about − 4‰) at FLFF7,22.

At SBHS, ground gas CO2 concentration, measured in the fumaroles, gives a high mean value of 95 ± 2%. Thermal waters have more DIC than at FLFF, with 31 ± 1 × 10−3 mol L−1 on average. Mean δ13C of − 0.72 ± 0.01‰ for gaseous CO2 and 0.5 ± 0.4‰ for DIC, confirms a metamorphic CO2 source (from 0 to − 2‰) at SBHS46. Finally, surface and ground gas temperatures are higher at FLFF compared with SBHS (Table 2).

Radon‒CO2 fluxes correlation

A general spatial agreement is found between radon flux and CO2 flux patterns both at FLFF (Supp. Fig. S2) and SBHS (Supp. Fig. S3). Combined radon and CO2 fluxes were measured exactly at the same point at 136 and 157 locations at FLFF and SBHS, respectively (see “Methods” section). High radon‒CO2 fluxes correlation coefficients of 0.83 ± 0.02 for FLFF and 0.80 ± 0.03 for SBHS suggest that CO2 is the main carrier gas of radon at both sites. Radon and CO2 fluxes are indeed strongly correlated over more than five orders of magnitude at both sites (Fig. 5), following a power-law relationship: ΦRn = 0.974ΦCO21.053 (R2 = 0.78) for FLFF, and ΦRn = 2.441ΦCO20.681 (R2 = 0.90) for SBHS. Despite a high dispersion of flux values for each site, systematic differences are larger than the dispersion and both sites can be discriminated. For a given CO2 flux, larger radon flux is observed at FLFF compared with SBHS, compatible with the larger radon source term of rocks at FLFF. The larger dispersion for FLFF may be explained by the larger range of radon source terms. As radon is carried by CO2 to the surface, radon transport mechanism is dominated by diffusion when CO2 flux remains small (< 100 g m−2 day−1), and by advection when CO2 flux increases47,56,58. For CO2 fluxes > 100 g m−2 day−1 in the advective domain (Fig. 5), radon fluxes are systematically larger at FLFF, and reach particularly high values for CO2 flux > 1000 g m−2 day−1, while, at SBHS, they tend to saturate. This confirms the reliability of our approach and suggests a shallower gas source at SBHS, a concept which is confirmed below by a detailed calculation.

Radon‒CO2 fluxes correlation for FLFF (in blue) and SBHS (in red). Only fluxes measured after the 2015 Gorkha earthquake are considered at SBHS. Diamond shows the data-set, dashed curve represents the average of the data, and solid curve is the calculation of the advective–diffusive radon transport model separately for each site using the depth of degassing constrained by an unbiased approach with 500 simulations (see “Methods” section). The bottom right inset represents the normalized χ2 coefficient as a function of the depth of the radon source, constraining the depth of CO2 degassing separately for each site (369 m for SBHS and 2632 m for FLFF). Model parameters are summarised in Table 3.

To interpret further Fig. 5, indeed, we consider a simplified model, less complex than the reality of the two sites, but able to reproduce the essence of the radon signature of CO2. We use an updated advective–diffusive transport model of radon carried upward by CO2 to the surface58 (see “Methods” section; Supp. Fig. S6). This model considers three phases for radon (gaseous, dissolved, and adsorbed) and three layers (soil, rock, and deep rock), and was modified to include temperature- and water-saturation-dependence of several radon parameters, including radon source term, an important modification for hydrothermal and volcanic sites. Since most parameters are assessed from field and laboratory data-sets, the model is able to represent both sites in term of radon transport from source(s) to surface. Deep rock layer is assumed saturated and its temperature is set to the vapour/liquid equilibrium temperature. For each layer, fixing porosity, water saturation, gas temperature, and radon source term, the depth of the deepest interface (rock ‒ deep rock interface) can be calculated using published equations58 (see “Methods” section; Table 3). We optimise this interface depth using a normalised χ2 coefficient calculated for each data-set (i number of data with CO2 flux > 100 g m−2 day−1), χ2 = Σi(ΦRnimeas‒ΦRnicalc)2/(σΦRni2 + σΦCO2i2), where, respectively, ΦRnmeas and ΦRncalc are measured and calculated radon fluxes, and σΦRn and σΦCO2 are one-sigma uncertainty on radon and CO2 fluxes. This interface corresponds to the maximum depth of the radon source, where CO2 velocity is high enough to carry radon before its decay, and therefore represents the maximum depth of radon-carrier degassed CO2. In some cases, it corresponds to the maximum depth of CO2 degassing. In other cases, CO2 degassing can be deeper and this depth can be seen as a minimum depth for degassed CO2.

Gas temperature and radon source term having larger effects on degassing depth (“Methods” section; Supp. Fig. S7), we vary these parameters of the soil and rock layers around the mean with 500 simulations. Minimum normalised χ2 coefficients give an optimized depth of degassing for each simulation, and the median of their distribution (Supp. Fig. S8) yields 2580 ± 180 m for FLFF and 380 ± 20 m for SBHS (Table 3 and inset of Fig. 5). Injecting these constrained depths, the model reproduces well the radon‒CO2 fluxes correlation over four to five orders of magnitude (Fig. 5). Furthermore, these depths match the general overview of CO2 transport at both sites, as described above. At FLFF, degassing depth of 2.6 km is compatible with the presence of a crystallised body of mica-rich syenite, which previous studies attributed a depth of 3‒4 km23. At SBHS, degassing depth of 380 m is consistent with a shallow CO2 reservoir, sensitive to crustal deformation and earthquakes8. While the interpretation of the estimated depth of degassing, when it is large, needs to be cautious, the one-order-of-magnitude difference in degassing depth between FLFF and SBHS is evidenced without doubt. This difference could also be examined through the prism of the CO2 source, as volcanic settings with mantellic and volcano-magmatic CO2 might have deeper roots than collisional settings with metamorphic CO2.

Discussion

The results shown above indicate that the most likely source of radon is from the rock. However, other radon sources have been considered: the thermal waters and the soil. At both sites, a water-degassing model58 (Supp. Fig. S9; see “Methods” section) or a purely diffusive model58 (Supp. Fig. S10; see “Methods” section) cannot account for the obtained estimated radon and CO2 discharges or reproduce the whole data-set, respectively. Thus, the rock layer appears the most representative radon source, controlling radon production and whose thickness constrains the degassing depth at both sites. The degassing depth appears nevertheless better constrained at SBHS, where depths greater than a few hundreds of metres are unlikely, whereas at FLFF, depths of ≈ 10 km might be possible (Supp. Figs. S8 and S11). Our model clearly interprets the unambiguous observation of the saturation of the radon flux at high CO2 flux as a smaller source thickness. At high CO2 velocities, the path length in the rock is not sufficient to recharge the CO2 flow with radon.

Our model takes into account the temperature dependence of radon source term and other radon parameters, but only experimentally constrained in the range 0‒100 °C (see “Methods” section), highlighting also limitations of our approach. Too little information on radon parameters variation with higher temperature is available64, motivating future investigations in that direction. Similarly, at such degassing depths (hundreds to thousands of metres), confining pressure is high, but, despite few studies on granitic13 and volcanic rocks12, radon source term variation with increasing pressure remains poorly known. Nevertheless, our model indicates that the variations of the source parameters or their heterogeneity are second-order effects. The largely dominating effect remains in all reasonable instances the path length, and hence the source depth.

The combination of field measurements of coupled CO2 and radon fluxes at the surface, laboratory characterisation of radon source term, and radon transport modelling have constrained the depth of CO2 degassing at two hydrothermal sites in different tectonic contexts and with different CO2 sources. Our results thus attest to the relevance of gas flux monitoring, particularly important at sites under near-critical conditions, sensitive to Earth’s deformation and earthquakes, which, contrary to what has been done in the past35,65, are not exclusively found in volcanic regions. For example, the Mw7.9 2015 Gorkha earthquake greatly affected gas emissions at SBHS, likely liberating CO2 previously stored in a crustal reservoir at shallow depths8. Our combined approach shows that emitted radon may have changed from a deeper (≈ 1000 m) to a shallower source (≈ 100 m) following the earthquake (Supp. Fig. S12).

Our combined study has revealed to be a powerful tool to determine the depth of degassing at FLFF, with mantellic and volcano-magmatic CO2 sources, and at SBHS, with a metamorphic CO2 source. To date, only few data are reported on CO2 and radon fluxes together47, almost all of them in collision context. Our approach should be systematically applied to sites in other tectonic contexts, such as rifting, reverse fault, strike-slip fault, or subduction, as well as in other volcanic environments. In addition, our model was found particularly sensitive for CO2 flux > 5000 g m−2 day−1, motivating future improvement in the measurement of such high fluxes. The presence of high gas fluxes, especially CO2, will be important to investigate in more details in the future, in particular when re-evaluating global carbon budgets9,66,67.

The radioactive gas radon, tracking CO2 degassing and diagnosing CO2 transport mechanisms, emerges as a powerful asset to characterise gaseous emissions and monitor earthquake-sensitive geosystems. In addition, the exceptionally high radon discharge from FLFF (≈ 9 GBq day−1), during a quiescent period, raises the issue of unconstrained radon emission from volcanoes, and suggests significant radon output from volcanic areas worldwide, especially when a large eruption occurs. Because emissions from volcanoes, unlike background diffusive soil emission, can reach above the atmospheric boundary layer, radon release from volcanoes worldwide may have substantial effects on atmosphere ionisation, aerosol formation, and climate68.

Methods

Radon flux

Radon-222 flux was measured at the surface using the accumulation chamber method46,56. Increase rate with time of radon activity concentration inside the chamber, directly related to radon flux, was measured using scintillation flasks (Algade, France) at both sites. Radon concentration in the flasks was inferred 3.5 h after sampling from counting in photomultipliers (CALEN™, Algade, France), regularly inter-calibrated in the laboratory. The method is robust, even in remote location48, and reliable where radon fluxes range over several orders of magnitude54. Radon flux is expressed in 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1. Associated uncertainty (Supp. Fig. S1a) was estimated from several systematic tests54. Relative experimental uncertainty ranges from 15% for fluxes ≈ 100 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1 to 30% for fluxes ≈ 10 × 10−3 and ≈ 10,000 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1. Radon fluxes were measured during stable weather conditions, in summer 2016 at FLFF, and in winters 2009‒2011, 2015, and 2016 at SBHS. A majority of points were measured several times (from 2 to 18 times); point-averages are arithmetic means. At FLFF, based on several measurements along time at selected points, variations of radon flux were < 10% and < 15% for fluxes < 1000 × 10−3 and > 10,000 × 10−3 Bq m−2 s−1, respectively. At SBHS, temporal variations of radon flux were generally < 30% for all fluxes. Total radon discharge, expressed in MBq day−1 (or Bq s−1), was estimated following the sequential Gaussian simulations (sGs) method69 with 100 equiprobable realizations. Radon fluxes measured at SBHS (gas zones 1 and 2) were published8,47,54 (Table 1).

CO2 flux

CO2 flux was measured at the surface using the accumulation chamber method70. Increase rate with time of CO2 concentration inside the chamber, directly related to CO2 flux, was measured by several portable sensors: at FLFF, two portable infrared fluxmeters (WestSystem™ CO2Flux, Italy), regularly calibrated by the manufacturer and inter-calibrated in the field; at SBHS, two portable infrared CO2 sensors and home-made accumulation chambers (Testo™ 535, Testo AG, Germany; Vaisala™ CARBOCAP® Hand-Held GM70, Finland), regularly inter-calibrated in the laboratory. Portable instruments are robust, even in remote location48 or during monsoon56, and reliable where CO2 fluxes range over six orders of magnitude32,54. CO2 flux is expressed in g m−2 day−1. Associated uncertainty (Supp. Fig. S1b) was estimated from previous assessments71 and systematic tests54. Relative experimental uncertainty ranges from 10% for low fluxes (10 g m−2 day−1) to 30% for large fluxes (10,000 g m−2 day−1). CO2 fluxes were measured during stable weather conditions, in summer 2016 at FLFF, and in winters 2015 to 2020 at SBHS. Every point was measured several times (from 2 to 26 times); point-averages are arithmetic means. At FLFF, only 4.3% temporal variation of CO2 flux was recorded at the 1-h continuous fluxmeter station GFUR2 during the 8-day-long field campaign (mean: 268 ± 12 g m−2 day−1). At SBHS, several points measured along time during the numerous field campaigns from November 2015 to January 2020 showed variations < 10% for fluxes < 100 g m−2 day−1 and < 20% for fluxes > 1000 g m−2 day−1. Total CO2 discharge, expressed in t day−1 (or mol s−1), was estimated following the sGs method69 with 100 equiprobable realizations. CO2 fluxes measured from November 2015 to January 2018 at SBHS (gas zones 1 and 2) were published8 (Table1).

Radon‒CO2 fluxes correlation

Only values of radon and CO2 fluxes obtained at the same measurement points were considered and no interpolation was used. This represents a total of 136 and 157 locations of combined fluxes for FLFF and SBHS, respectively.

Radon sources

Effective radium-226 concentration (ECRa)

Radon-222 source in porous materials is the effective radium-226 concentration, expressed in Bq kg−1, i.e. the product of the bulk radium concentration CRa and the emanation coefficient E, probability that a radium atom produces a radon atom in the pore space. ECRa was measured in the laboratory on rock and soil samples using a radon accumulation method60,72,73. The sample was placed in a hermetically closed container. After a 5-to-18-day accumulation time, radon concentration of the free air inside the accumulator was determined after sampling using a scintillation flask (Algade, France) and counting in a photomultiplier (CALEN™, Algade, France). A minimum of three measured values per sample were averaged. Relative experimental uncertainty ranges from 3% for ECRa ≈ 30 Bq kg−1 to 10% for ECRa ≈ 1 Bq kg−1. SBHS data were partly published50,54.

Ground radon concentration

Ground radon-222 concentration, expressed in Bq m−3, was measured at FLFF at 60‒100 cm depth by gas pumping using a portable RAD7 detector (Durridge Company, Inc., USA). At SBHS, it was measured at 100 cm depth using continuous radon concentration probes (Barasol™ and BMC2™, Algade, France). All these instruments are based on the detection of alpha particles by a silicon detector material. Sensitivity, inter-comparison dispersion, and overall common uncertainty are 4 and 50 Bq m−3, 5% and 3%, and 5% and 5%, for RAD7 and continuous instruments, respectively. SBHS data were partly published54,57.

Radon in water bubbles

Radon-222 concentration in water bubbles was measured after accumulation of gas in small containers above the water pond, sampling using scintillation flasks, and counting in photomultipliers. Relative experimental uncertainty is similar to that of ECRa method.

Radon and radium in water

Radon-222 concentration in water, expressed in Bq L−1, was measured by the emanometry method58,62. The water was sampled in a container, hermetically closed after sampling. After shaking, sampling of the air inside the container was done by a scintillation flask and counting using a photomultiplier. Relative experimental uncertainty ranges from 5 to 30%. Two or more replicates were performed at each location. Radium-226 concentration in water, expressed in 10−3 Bq L−1, was measured following the radon method58,62,74. After water sampling in the field, the container was kept closed in the laboratory for 2 months minimum before measurement. Relative experimental uncertainty ranges from 5% for CRa ≈ 100 × 10−3 Bq L−1 to 10% for CRa ≈ 10 × 10−3 Bq L−1 (Table 2).

CO2 sources

Ground CO2 concentration

Ground CO2 concentration, expressed in vol.%, was measured at FLFF at 60‒100 cm depth by gas pumping using a portable infrared sensor (Geotechnical Instruments, UK) with 0‒100 vol% measurement range. At SBHS, gas was sampled using evacuated glass tubes and CO2 concentration was determined manometrically54. Absolute experimental uncertainty ranges from 0.5 to 3% for the infrared cell and from 0.1 to 1% using the mass spectrometer. Only 2007‒2018 SBHS data were partly published8,46,47,54.

δ13C of CO2 gas

The gas was collected using accumulation chambers and evacuated glass tubes8,47,54. Gas samples were analysed for molecular composition in the laboratory45. Carbon isotopic ratio of gaseous CO2, δ13C, expressed in ‰ and defined relative to the standard value of Pee Dee belemnite (V-PDB), was determined after off-line purification using a Finnigan™ MAT-253 mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., Germany) at CRPG (Nancy, France). Repeatability and absolute experimental uncertainty are 0.1 ‰. FLFF data were partly published7,22; SBHS 2007‒2018 data were published8,46,47,54.

Dissolved inorganic carbon concentration and δ13C of dissolved CO2

Water was sampled using 12-mL screw cap vials. Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) concentration, expressed in 10−3 mol L−1, was determined using a gas chromatograph coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (GCIRMS, GV 2003, GV Instruments, UK) at IPGP (Paris, France). Relative experimental uncertainty ranges from 1 to 2%. δ13C of dissolved CO2 in water, expressed in ‰ relative to V-PDB, was determined using the same spectrometer at IPGP. Absolute experimental uncertainty is 0.1‰. SBHS data were published8; FLFF data were taken from the literature24 (Table 2).

Surface and ground temperature

Surface temperature

At FLFF, temperature was measured systematically at surface using a thermocouple (Testo 925™, Testo AG, Germany). Absolute experimental uncertainty is 0.1 °C. At SBHS, temperature was measured at the surface using regularly inter-calibrated, autonomous sensors (SB39, Seabird™, USA). Their sensitivity is better than 3.5 × 10−3 °C54.

Ground temperature

At FLFF, temperature was measured at the top of 60‒100 cm holes with the same thermocouple used for surface temperature. Absolute experimental uncertainty is 0.1 °C. At SBHS, temperature was measured at 100 cm depth using SB39 sensors, recording at 30 s intervals (Table 2).

Radon transport modelling

Diffusive–advective radon transport model

The model considers that degassing of hydrothermal CO2 is initiated at depth, provided it travels fast enough relative to the radon-222 half-life. After degassing, CO2 percolates through rock and soil layers until it reaches the surface, carrying radon produced by these layers along its pathway. We consider soil, rock, and deep rock layers from surface in a semi-infinite porous medium (Supp. Fig. S6). For radon, we consider gaseous, dissolved, and adsorbed phases with equation terms of diffusion, advection, radioactive decay, and production, that are implemented analytically. We use transport Eqs. (B2)–(B4) of Ref.58 without modification. Using Eqs. (B6)–(B11) or Eqs. (B13)–(B17) for large advection (Ref.58), we solve the following steady-state 1D equation for each layer i:

where \({D}_{\textrm{S}i}=\frac{{\upvarepsilon }_{\mathrm{a}i}{D}_{\mathrm{e}i}^{\mathrm{a}}+{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{w}i}{\kappa }_{\mathrm{w}i}{D}_{\mathrm{e}i}^{\mathrm{w}}}{{\upvarepsilon }_{\mathrm{a}i}+{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{w}i}{\kappa }_{\mathrm{w}i}+{k}_{{\text{d}}i}\rho }\), \({T}_{\mathrm{S}i}=\frac{u+I{\kappa }_{\mathrm{w}i}}{{\upvarepsilon }_{\mathrm{a}i}+{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{w}i}{\kappa }_{\mathrm{w}i}+{k}_{{\text{d}}i}\rho }\) and equilibrium radon concentration \({C}_{\mathrm{a}i}^{0}=\frac{{EC}_{{\text{Ra}}i}\uprho }{{\upvarepsilon }_{\mathrm{a}i}+{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{w}i}{\kappa }_{\mathrm{w}i}+{k}_{{\text{d}}i}\rho }\), with u the Darcy velocity related to the carrier CO2 flux and I the water infiltration (for more details see Supp. Fig. S6 and Ref.58). Here, for given layer i, we introduce empirical relations for porosity- and water-saturation-dependent effective diffusion coefficients75 (\({D}_{\mathrm{e}i}^{\mathrm{a}}=1.1\times {10}^{-5}\times {\upvarepsilon }_{\mathrm{a}i}\mathrm{exp}(-6{S}_{\mathrm{w}i}{\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{a}i}-6{{S}_{\mathrm{w}i}}^{14 {\upvarepsilon }_{\mathrm{a}i}})\) and \({D}_{\mathrm{e}i}^{\mathrm{w}}=1.1\times {10}^{-8}\times {\upvarepsilon }_{\mathrm{w}i}\mathrm{exp}(-6\left(1-{S}_{\mathrm{w}i}\right){\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{w}i}-6(1-{{S}_{\mathrm{w}i})}^{14 {\upvarepsilon }_{\mathrm{w}i}})\)), temperature-dependent water/air partition58 and adsorption coefficients76 (\({\kappa }_{{\text{w}}i}=0.104+0.416\mathrm{exp}\left(- 0.0491{T}_{i}\right)\) and \({k}_{{\text{d}}i}={k}_{\mathrm{d}i}^{0}\mathrm{exp}\left(\frac{19500}{8.314}(\frac{1}{{T}_{i}}-\frac{1}{253.15})\right)\) with \({k}_{\mathrm{d}1}^{0}=0.181\) and \({k}_{\mathrm{d2,3}}^{0}=0.258\)) and water-saturation- and temperature-dependent radon source terms73,77 (\({EC}_{{\text{Ra}}1}={EC}_{\mathrm{Ra}1}^{0}(32.22{\text{exp}}\left(-1.88{S}_{\mathrm{w}1}\right)-31.43{\text{exp}}\left(- 1.98{S}_{\mathrm{w}1}\right))(1+0.01(0.7875{T}_{1}-15.75))\)) and \({EC}_{{\text{Ra}}\mathrm{2,3}}={EC}_{\mathrm{Ra2,3}}^{0}(32.22{\text{exp}}\left(- 1.88{S}_{\mathrm{w}1}\right)-31.43{\text{exp}}\left(- 1.98{S}_{\mathrm{w}1}\right))(1+0.01(0.5535{T}_{1}-11.07))\)). For both sites, we fix parameters according to field and laboratory data-sets, such as soil thickness (1 m), soil and rock porosity and water saturation (deep rock is assumed saturated), gas temperature, and radon source term; we calculate water–air partition and adsorption coefficients; and we correct radon source term. For a given CO2 flux, we calculate a radon flux using Eqs. (B12) or (B18) for large advection (Ref.58). We then compare the calculated and measured radon fluxes using a χ2 coefficient (see text) to estimate the best depth of degassing (interface between the rock and deep rock layers). We separately tested the sensitivity of the degassing depth to several parameters considering an acceptable range of values (Supp. Fig. S7). For the soil and deep rock layers, varying total porosity (soil: 0.01‒0.4, rock: 0.01‒0.15), water saturation (0.1‒0.9), gas temperature and radon source term (50% around the mean; see Table 2) has low effect on the degassing depth. However, such variations for the rock layer yield larger effects (Supp. Fig. S7), in particular for gas temperature and radon source term. Then, to explore the phase space, similarly to a Bayesian Monte Carlo unbiased approach, we generated 500 independent models, varying gas temperature and radon source term in the soil and rock layers, with Gaussian distributions, to estimate the depth of degassing (see text; Table 3). The final degassing depth estimate is taken as the median value from the 500 simulations (Supp. Fig. S8).

Alternative models

Other modelling approaches were also used. A first analytical model58 considers that a given fraction f of CO2 degasses together with radon from water springs at or near the surface. We use Eqs. (A1)–(A7) of Ref.58 without modification. Another analytical model58 considers that radon transport is only governed by diffusion, using the same equations given above with u = 0. We use Appendix C of Ref.58. For these two alternative models, the full description and the equations are given in a previous contribution58.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Irwin, W. P. & Barnes, I. Tectonic relations of carbon dioxide discharges and earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. 85, 3115–3121 (1980).

Miller, S. M. Aftershocks are fluid-driven and decay rates controlled by permeability dynamics. Nat. Commun. 11, 5787 (2020).

Tamburello, G., Pondrelli, S., Chiodini, G. & Rouwet, D. Global-scale control of extensional tectonics on CO2 earth degassing. Nat. Commun. 9, 4608 (2018).

Sibson, R. H. An episode of fault-valve behaviour during compressional inversion?—The 2004 MJ6.8 Mid-Niigata Prefecture, Japan, earthquake sequence. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 257, 188–199 (2007).

Cappa, F., Rutqvist, J. & Yamamoto, K. Modeling crustal deformation and rupture processes related to upwelling of deep CO2-rich fluids during the 1965–1967 Matsushiro earthquake swarm in Japan. J. Geophys. Res. 114, B10304 (2009).

Chiodini, G. et al. Correlation between tectonic CO2 Earth degassing and seismicity is revealed by a 10-year record in the Apennines, Italy. Sci. Adv. 6, 2938 (2020).

Viveiros, F. et al. Soil CO2 emissions at Furnas volcano, São Miguel Island, Azores archipelago: Volcano monitoring perspectives, geomorphologic studies, and land use planning application. J. Geophys. Res. 115, B12208 (2010).

Girault, F. et al. Persistent CO2 emissions and hydrothermal unrest following the 2015 earthquake in Nepal. Nat. Commun. 9, 2956 (2018).

Burton, M. R., Sawyer, G. M. & Granieri, D. Deep carbon emissions from volcanoes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 75, 323–354 (2013).

Igarashi, G. et al. Ground-water anomaly before the Kobe earthquake in Japan. Science 269, 60–61 (1995).

Richon, P. et al. Radon anomaly in the soil of Taal volcano, the Philippines: A likely precursor of the M 7.1 Mindoro earthquake (1994). Geophys. Res. Lett. 30(9), 1481 (2003).

Tuccimei, P., Mollo, S., Vinciguerra, S., Castelluccio, M. & Soligo, M. Radon and thoron emission from lithophysae-rich tuff under increasing deformation: An experimental study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L05305 (2010).

Girault, F., Schubnel, A. & Pili, É. Transient radon signals driven by fluid pressure pulse, micro-crack closure, and failure during granite deformation experiments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 474, 409–418 (2017).

Geller, R. J. Shake-up time for Japanese seismology. Nature 472, 407–409 (2011).

Parks, M. M. et al. Distinguishing contributions to diffuse CO2 emissions in volcanic areas from magmatic degassing and thermal decarbonation using soil gas 222Rn–δ13C systematics: Application to Santorini volcano, Greece. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 377–378, 180–190 (2013).

Neri, M. et al. Soil radon measurements as a potential tracer of tectonic and volcanic activity. Sci. Rep. 6, 24581 (2016).

D’Alessandro, W. et al. Carbon dioxide and radon emissions from the soils of Pantelleria island (Southern Italy). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 362, 49–63 (2018).

Bini, G. et al. Deep versus shallow sources of CO2 and Rn from a multiparametric approach: the case of the Nisyros caldera (Aegean Arc, Greece). Sci. Rep. 10, 13782 (2020).

Moore, R. B. Geology of Three Late Quaternary Stratovolcanoes on São Miguel, Azores (USGS Technical Report, 1991).

Guest, J. et al. Volcanic geology of Furnas Volcano, São Miguel, Azores. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 92, 1–29 (1999).

Gaspar, J. L. et al. Volcanic Geology of São Miguel Island (Azores Archipelago) Vol. 44, 125–134 (Geological Society, 2016).

Caliro, S., Viveiros, F., Chiodini, G. & Ferreira, T. Gas geochemistry of hydrothermal fluids of the S. Miguel and Terceira Islands, Azores. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 168, 43–57 (2015).

Jeffery, A. J. et al. Temporal evolution of a postcaldera, mildly peralkaline magmatic system: Furnas volcano, São Miguel, Azores. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 171, 42 (2016).

Cruz, J. V., Coutinho, R. M., Carvalho, M. R., Oskarsson, N. & Gislason, S. R. Chemistry of waters from Furnas volcano, São Miguel, Azores: fluxes of volcanic carbon dioxide and leached material. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 92, 151–167 (1999).

Zandomeneghi, D., Almendros, J., Ibáñez, J. M. & Saccorotti, G. Seismic tomography of Central São Miguel, Azores. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 167, 8–18 (2008).

Montesinos, F. G., Camacho, A. G. & Vieira, R. Analysis of gravimetric anomalies in Furnas caldera (São Miguel, Azores). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 92, 67–81 (1999).

Hogg, C. et al. 3-D interpretation of short-period magnetotelluric data at Furnas Volcano, Azores Islands. Geophys. J. Int. 213, 371–386 (2018).

Yogeshwar, P. et al. Innovative boat-towed transient electromagnetics—Investigation of the Furnas volcanic lake hydrothermal system, Azores. Geophysics 85, E41–E56 (2020).

Ferreira, T. & Oskarsson, N. Chemistry and isotopic composition of fumarole discharges of Furnas caldera. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 92, 169–179 (1999).

Jean-Baptiste, P. et al. Helium isotopes in hydrothermal volcanic fluids of the Azores archipelago. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 281, 70–80 (2009).

DROTRH, INAG. Plano Regional da Agua 414 (Direcção Regional do Ordenamento do Teritório e Recursos Hídricos (DROTRH) / Instituto da água (INAG), 2001).

Viveiros, F., Ferreira, T., Cabral Vieira, J., Silva, C. & Gaspar, J. L. Environmental influences on soil CO2 degassing at Furnas and Fogo volcanoes (São Miguel Island, Azores archipelago). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 177, 883–893 (2008).

Pedone, M. et al. Total (fumarolic + diffuse soil) CO2 output from Furnas volcano. Earth Planets Space 67, 174 (2015).

Bagnato, E. et al. Hg and CO2 emissions from soil diffuse degassing and fumaroles at Furnas Volcano (São Miguel Island, Azores): Gas flux and thermal energy output. J. Geochem. Explor. 190, 39–57 (2018).

Viveiros, F. et al. Periodic behavior of soil CO2 emissions in diffuse degassing areas of the Azores archipelago: Application to seismovolcanic monitoring. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 7578–7597 (2014).

Prytulak, J. et al. Melting versus contamination effects on 238U–230Th–226Ra and 235U–231Pa disequilibria in lavas from São Miguel, Azores. Chem. Geol. 381, 94–109 (2014).

Silva, C., Ferreira, T., Viveiros, F. & Allard, P. Soil radon (222Rn) monitoring at Furnas Volcano (São Miguel, Azores): Applications and challenges. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 224, 659–686 (2015).

Gaspar, J. L. et al. (eds) Volcanic Geology of São Miguel Island (Azores Archipelago) Vol. 44, 197–211 (Geological Society, 2015).

Viveiros, F., Ferreira, T., Silva, C. & Gaspar, J. L. Meteorological factors controlling soil gases and indoor CO2 concentration: A permanent risk in degassing area. Sci. Total Environ. 407, 1362–1372 (2009).

Ader, T. et al. Convergence rate across the Nepal Himalaya and interseismic coupling on the Main Himalayan Thrust: Implications for seismic hazard. J. Geophys. Res. 117, B04403 (2012).

Grandin, R. et al. Rupture process of the Mw=7.9 2015 Gorkha earthquake (Nepal): Insights into Himalayan megathrust segmentation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8373–8382 (2016).

Bollinger, L., Avouac, J.-P., Cattin, R. & Pandey, M. R. Stress buildup in the Himalaya. J. Geophys. Res. 109, B11405 (2004).

Upreti, B. N. An overview of the stratigraphy and tectonics of the Nepal Himalaya. J. Asian Earth Sci. 17, 577–606 (1999).

Becker, J. A., Bickle, M. J., Galy, A. & Holland, T. J. B. Himalayan metamorphic CO2 fluxes: Quantitative constraints from hydrothermal springs. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 265, 616–629 (2008).

Evans, M. J., Derry, L. A. & France-Lanord, C. Degassing of metamorphic carbon dioxide from the Nepal Himalaya. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q04021 (2008).

Perrier, F. et al. A direct evidence for high carbon dioxide and radon-222 discharge in Central Nepal. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 278, 198–207 (2009).

Girault, F. et al. Large-scale organization of carbon dioxide discharge in the Nepal Himalayas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6358–6366 (2014).

Girault, F., Koirala, B. P., Bhattarai, M. & Perrier, F. Radon and carbon dioxide around remote Himalayan thermal springs. Geol. Soc. Lond. S. P. 451, 155–181 (2018).

Kohn, M. J. P-T-t data from central Nepal support critical taper and repudiate large-scale channel flow of the Greater Himalayan Sequence. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 120, 259–273 (2008).

Girault, F. et al. Effective radium concentration across the Main Central Thrust in the Nepal Himalayas. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 98, 203–227 (2012).

Dhital, M. R. Geology of the Nepal Himalaya. Regional Perspective of the Classic Collided Orogen (Springer, 2015).

Unsworth, M. J. et al. Crustal rheology of the Himalaya and Southern Tibet inferred from magnetotelluric data. Nature 438, 78–81 (2005).

Byrdina, S. et al. Dipolar self-potential anomaly associated with carbon dioxide and radon flux at Syabru-Bensi hot springs in central Nepal. J. Geophys. Res. 114, B10101 (2009).

Girault, F. et al. The Syabru-Bensi hydrothermal system in central Nepal: 1. Characterization of carbon dioxide and radon fluxes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 4017–4055 (2014).

Brunello, C. F. et al. Annually resolved monsoon onset and withdrawal dates across the Himalayas derived from local precipitation statistics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088420 (2020).

Girault, F., Koirala, B. P., Perrier, F., Richon, P. & Rajaure, S. Persistence of radon-222 flux during monsoon at a geothermal zone in Nepal. J. Environ. Radioact. 100, 955–964 (2009).

Richon, P. et al. Temporal signatures of advective versus diffusive radon transport at a geothermal zone in Central Nepal. J. Environ. Radioact. 102, 88–102 (2011).

Girault, F. & Perrier, F. The Syabru-Bensi hydrothermal system in central Nepal: 2. Modeling and significance of the radon signature. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 4056–4089 (2014).

Sinclair, A. J. Selection of threshold values in geochemical data using probability graphs. J. Geochem. Explor. 3, 129–149 (1974).

Perrier, F., Girault, F. & Bouquerel, H. Effective radium concentration in rocks, soils, plants, and bones. Geol. Soc. Lond. S. P. 451, 113–129 (2018).

Girault, F. et al. Substratum influences uptake of radium-226 by plants. Sci. Total Environ. 766, 142655 (2021).

Girault, F., Perrier, F. & Przylibski, T. A. Radon-222 and radium-226 occurrence in water: A review. Geol. Soc. Lond. S. P. 451, 131–154 (2018).

Rennert, T. & Pfanz, H. Hypoxic and acidic—Soils on mofette fields. Geoderma 280, 73–81 (2016).

Nicolas, A. et al. Radon emanation from brittle fracturing in granites under upper crustal conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 5436–5443 (2014).

Granieri, D., Chiodini, G., Marzocchi, W. & Avino, R. Continuous monitoring of CO2 soil diffuse degassing at Phlegraean Fields (Italy): Influence of environmental and volcanic parameters. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 212, 167–179 (2003).

Aiuppa, A., Fischer, T. P., Plank, T. & Bani, P. CO2 flux emissions from the Earth’s most actively degassing volcanoes, 2005–2015. Sci. Rep. 9, 5442 (2019).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3269–3340 (2020).

Lee, S.-H. et al. Particle formation by ion nucleation in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere. Science 301, 1886–1889 (2003).

Cardellini, C., Chiodini, G. & Frondini, F. Application of stochastic simulation to CO2 flux from soil: Mapping and quantification of gas release. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 2425 (2003).

Chiodini, G., Cioni, R., Guidi, M., Raco, B. & Marini, L. Soil CO2 flux measurements in volcanic and geothermal areas. Appl. Geochem. 13, 543–552 (1998).

Carapezza, M. L. & Granieri, D. CO2 soil flux at Vulcano (Italy): Comparison between active and passive methods. Appl. Geochem. 19, 73–88 (2004).

Girault, F. & Perrier, F. Measuring effective radium concentration with large numbers of samples. Part I—Experimental method and uncertainties. J. Environ. Radioact. 113, 177–188 (2012).

Girault, F. & Perrier, F. Measuring effective radium concentration with large numbers of samples. Part II—General properties and representativity. J. Environ. Radioact. 113, 189–202 (2012).

Perrier, F., Aupiais, J., Girault, F., Przylibski, T. A. & Bouquerel, H. Optimized measurement of radium-226 concentration in liquid samples with radon-222 emanation. J. Environ. Radioact. 157, 52–59 (2016).

Rogers, V. C. & Nielson, K. K. Multiphase radon generation and transport in porous materials. Health Phys. 60, 807–815 (1991).

Meslin, P.-Y., Sabroux, J.-C., Bassot, S. & Chassefière, E. Experimental study of radon production and transport in an analogue for the Martian regolith. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 2256–2270 (2011).

Girault, F. & Perrier, F. Heterogeneous temperature sensitivity of effective radium concentration from various rock and soil samples. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 1619–1626 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to IVAR (Azores, Portugal) and DMG (Nepal) for help and support during the different fieldworks and over the years. We are thankful to the organizers and participants to the fieldwork in the Azores in June 2016: André Revil (ISTerre Chambéry, France), Damien Jougnot (Sorbonne Université, France), Volker Rath, Colin Hogg, and Duigu Kiyan (Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Ireland), and Niels Grobbe (University of Hawai’i, USA). Nabin Ghising Tamang is thanked for managing the authorizations and for his fieldwork participation at SBHS. Hélène Bouquerel and Roxane Ferry are thanked for the measurements of CO2 fluxes at SBHS in May 2016 and January 2018, respectively. We thank Buddha Lama, Nabin Tamang, Dawa Tamang, Om Bahadur Tharum, and Niraj Jairu for their help in the measurement of CO2 and radon fluxes and for the fieldwork logistics at SBHS. The Deep Carbon Observatory (DCO) is thanked for having initiated the collaboration between IVAR and IPGP research groups on carbon emissions through the participation of F.G. to the Early Career Scientist Workshop held in September 2015 at the University of the Azores. Financial support for the work at FLFF was provided in 2016 by a TelluS-ALEAS INSU CNRS grant to S.B. and André Revil. Recent elaboration of the data from FLFF was carried out under MAGAT project (Ref. CIRCNA/OCT/2016/2019). The work at SBHS was supported financially by public and private funding of the IPGP team “Physics of Natural Sites”, partly complemented in 2016 by a TelluS-SYSTER INSU CNRS grant to F.G. and in 2020 by LabEx UnivEarthS Frontier MYSTHIC (ANR-10-LABX-0023 and ANR-18-IDEX-0001) lead by F.G. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that improved the overall quality of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.G., F.V. and S.B. designed this work. F.G., F.V., and F.P. wrote the paper. For the FLFF data-set: F.G. measured radon and CO2 fluxes, dissolved radon concentration in water, ECRa in the laboratory, and collected gas and water samples; F.V. measured CO2 flux and ground temperature; C.S. measured ground radon and CO2 concentrations and temperature; J.E.P. measured radon and CO2 fluxes; F.V., C.S., and J.E.P. collected soil and rock samples; C.F.-L. measured carbon isotopic composition of the gas phase in the laboratory; F.P. measured ECRa and dissolved radium concentration in the laboratory. For the SBHS data-set: F.G. measured radon and CO2 fluxes, dissolved radon concentration in water, ECRa in the laboratory, and collected gas, water, soil, and rock samples; S.T. measured CO2 fluxes and collected water in 2020; L.B.A., B.P.K., and M.B. participated to field CO2 flux measurements; P.A. measured carbon isotopic composition and dissolved inorganic concentration of the water phase in the laboratory. C.F.-L. measured carbon isotopic composition of the gas phase in the laboratory; F.P. measured radon fluxes, dissolved radon and radium concentrations in water, and ECRa in the laboratory. F.G. processed Figs. 2, 5, and Figs. S1–S10. F.V. processed Figs. 1a, 3 and 4. S.T. processed Fig. 1b. F.G. and F.P. did the modelling. V.Z., J.V., and S.B. discussed the modelling. All the authors discussed the data-sets and amended the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Girault, F., Viveiros, F., Silva, C. et al. Radon signature of CO2 flux constrains the depth of degassing: Furnas volcano (Azores, Portugal) versus Syabru-Bensi (Nepal Himalayas). Sci Rep 12, 10837 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14653-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14653-5

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.