Abstract

Cretaceous represents one of the hottest greenhouse periods in the Earth's history, but some recent studies suggest that small ice caps might be present in non-polar regions during certain periods in the Early Cretaceous. Here we report extremely negative δ18O values of −18.12‰ to −13.19‰ for early Aptian hydrothermal zircon from an A-type granite at Baerzhe in northeastern China. Given that A-type granite is anhydrous and that magmatic zircon of the Baerzhe granite has δ18O value close to mantle values, the extremely negative δ18O values for hydrothermal zircon are attributed to addition of meteoric water with extremely low δ18O, mostly likely transported by glaciers. Considering the paleoaltitude of the region, continental glaciation is suggested to occur in the early Aptian, indicating much larger temperature fluctuations than previously thought during the supergreenhouse Cretaceous. This may have impact on the evolution of major organism in the Jehol Group during this period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

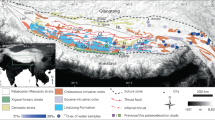

Although the Cretaceous is reputed to have had a hot, greenhouse climate1,2,3,4, its entire history is not well documented. Most published isotopic data, paleobiogeography of terrestrial and marine organisms, leaf physiognomy and the distribution of climatic-sensitive sediments have been interpreted to indicate that temperatures in the Early Cretaceous were much warmer than present, especially at high latitudes2,3. However, there are some paleontological records implying a cool climate at that time5,6,7. This interpretation is also supported by other indications of cool intervals from the late Barremian to the early Albian of the Early Cretaceous6,7, with an estimated mean air temperatures comparable to the present day “icehouse” — about 10 ± 4°C at mid-latitudes (~42°N) in Asia8, implying small polar ice caps. Concrete evidence for these ice caps is sparse, however, because the subsequent oscillation between greenhouse and icehouse conditions may efficiently eliminated the surface records of paleo-glaciation5. Here we provide new δ18O data of zircon from the Baerzhe A-type granite in northeastern China at the paleolatitude of ~ 45°N, which indicate a contribution from continental glacial meltwater (Fig. 1).

Geographical positions of the Baerzhe intrusion and the deposits of Jehol Biota.

Inset is the distribution of the Jehol ecosystem (radial circle) in the paleogeographic map of eastern Asia in the Early Cretaceous, modified from Zhou et al57. The Jehol Group is comprised of the Yixian and Jiufotang Formations, which crop out in western Liaoning, northern Hebei and southeastern Inner Mongolia57. The paleolatitude of the Baerzhe A-type granite is ca. 45°N. Abbreviations refer to major tectonic divisions: EUR, Europe; INC, Indo-China; IND, India; JUN, Junggar; KAZ, Kazakhstan; LH, Lhasa; MON, Mongolian; NCB, north China; QA, Qiadam; QI, Qiangtang; SCB, south China; SH, Shan Thai; SIB, Siberian; and TAR, Tarim.

The Baerzhe A-type granite is located in southeastern Great Khingan Mountains, northeastern China (Fig. 1), which intruded into the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous igneous rocks, in the eastern part of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt9. The Late Jurassic volcanic rocks consist of andesite, andesitic tuff and intermediate-acid volcanic clastic rock10. The Early Cretaceous igneous rocks include rhyolites and andesitic tuffs that unconformably overlying the Late Jurassic volcanic rocks. The giant Baerzhe Zr–REE–Nb deposit is hosted in the albite-rich phase, which occurs in the upper section of the Baerzhe granite, while the lower section is barren (or weakly mineralized). Pegmatites were discovered on the top of the mineralized granite11,12. The granite consists mainly of microcline, quartz, arfvedsonite and albite, whereas the proportions, grain sizes and crystal forms of rock-forming minerals differ in the mineralized and barren counterparts. The mineralized granite contains much more aegirine and albite and less arfvedsonite, moreover, the crystals are larger and slightly more euhedral, which are in striking contrast to the barren granite. The occurrence of abundant miarolitic cavities suggests a shallow level emplacement (< 2 km)13 and highly evolved9,14. Zircon is an important ore mineral in the Zr–REE–Nb deposit, with both magmatic and hydrothermal origins. The hydrothermal zircon we identified in Baerzhe is characterized by features originated from the magmatic-hydrothermal transition systems of the highly evolved granitic pluton9, which include: (1) tetragonal dipyramidal in morphology that is a relatively low-temperature zircon type from evolved alkaline granite15,16; (2) murky and featureless in textures and LREE-rich and high common lead in compositions are common characteristics of zircon grains that directly crystallized from Zr-saturated hydrothermal fluids17,18.

Results

Magmatic zircon grains from the A-type granite occur as crystals of prismatic morphology with oscillatory zonation in cathodoluminescence (CL) images and are depleted in LREE (Supplementary Table S1). They have concordant 206Pb/238U ages of 123.9 ± 1.2 Ma (2σ, MSWD = 0.65, n = 17) (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2). They have positive δ18O values of 2.79 to 5.10‰ (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S3), slightly lower than values of 5.3 ± 0.3‰ for normal mantle zircon δ18O values19. They have εHf(t) values ranging from 1.51 to 12.6 (Supplementary Table S4). Quartz phenocrysts from the granite exhibit an average δ18O value of 5.37 ± 0.54‰ (1σ) (Supplementary Table S5). When paired with a weighted average δ18O value of 3.47 ± 0.11‰ (1σ) for the magmatic zircon, this yields an O isotope temperature of 1030°C (Supplementary Fig. S8)20. This temperature corresponds to the highest value for homogenization temperatures of primary melt inclusions (750 to 1030°C) in quartz phenocrysts12, suggesting O isotope equilibrium between the magmatic quartz and zircon in the granite.

Zircon U-Pb ages for the Baerzhe A-type granite and its coincidence with the Jehol Biota deposits, drop of global sea-level and negative shift of carbon isotopes for Pacific sediments.

The ages range from 124.1 ± 0.3 Ma to 122.9 ± 0.7 Ma of a tuff in the main fossil bed of Jehol Biota in the Yixian Formation is highlighted with gray58. The low value on the eustatic curve in the early Aptian is attributed to glacioeustasy37. The carbon isotopes curves also show a significant negative excursion at ca. 124 Ma38.

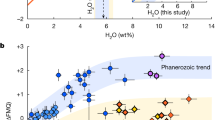

Plot of εHf(t) versus δ18O values for magmatic and hydrothermal zircon in this study, showing remarkable shifts of oxygen isotopes corresponding to incorporation of continental glacial meltwater into the alkaline magma.

VSMOW denotes the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water. The normal mantle zircon δ18O value is 5.3 ± 0.3‰19. The consistent εHf(t) values and great shift of δ18O values from the magmatic zircon to the hydrothermal zircon were caused by the incorporation of continental glacial water. Note that the three middle spots of magmatic zircon show a minor hydrothermal influence.

Hydrothermal zircon grains from the Baerzhe ore deposit occur as crystals of tetragonal dipyramids, which are murky in CL images and enriched in LREE (Supplementary Table S1). They have concordant 206Pb/238U age of 123.5 ± 3.2 Ma (2σ, MSWD = 0.37, n = 7) (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S2) and have εHf(t) values ranging from 2.54 to 7.62 (Supplementary Table S4). Most analyses for the hydrothermal zircons yield extremely negative δ18O values of −18.12‰ to −13.19‰ (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S3), which are significantly lower than magmatic zircon from other Cretaceous granite in the adjacent area21,22. To our knowledge, −18.12‰ is the lowest δ18O value of zircon from granite so far reported23,24,25,26,27,28. It is significantly lower than negative δ18O values of −14.4 to −10.0‰ for magmatic garnet from granite27 and −10.9 to −7.8‰ for metamorphic and magmatic zircons from metabasite and metagranite25,28 in the Dabie-Sulu orogenic belt. Such negative δ18O values from the Dabie-Sulu rocks have been attributed to high-temperature hydrothermal alteration in a rift tectonic zone by continental glacial meltwater prior to the Snowball Earth event26,27. Since O diffuses very slowly in zircon29,30, crystalline zircon is capable of preserving the original δ18O signature of its source23,25. The extremely negative 18O values for the hydrothermal zircon from the highly evolved Baerzhe pluton indicate that unusual 18O-depleted water was incorporated into the Zr-saturated hydrothermal fluid in which the hydrothermal zircon was crystallized.

Discussion

Fluid δ18O values responsible for the negative δ18O hydrothermal zircon grains are estimated to be lower than −15.23‰ at 600°C, according to the O isotope fractionation factor between zircon and water20. If hydrothermal zircon is crystallized in hydrothermal fluid consisting of a mixture between a magmatic exsolved fluid and a surface water, δ18O value for the participated surface water should be lower than the lowest measured δ18O value of zircon that we report. We estimate that the water that caused the extremely 18O depletion of hydrothermal zircon could have been as low as −17‰ to −34‰, assuming 10% to 50% of the fluid was magmatic exsolved fluid. The only significant terrestrial reservoir with such negative δ18O values is the highly fractionated meteoric water and its frozen product (continental ice sheet)26,31.

The most plausible source of such negative δ18O values can be expected from continental glacier melt water. The Baerzhe A-type granite is located in NE Asia at mid-latitude and not far away from the Pacific Ocean (< 700 km) since the Jurassic (Fig. 1) based on the paleomagnetic results32. The current altitude of the Baerzhe region is 850 m. This region did not experience major denudation as indicated by Late Jurassic calderas remnants33, such that the paleo-altitude of the Baerzhe region is inferred to be ~ 2 km or less34, which was exclude of intra-continental high mountains. δ18O values for present-day precipitation at the Baerzhe region is estimated to be about −10‰35 and it is likely to be more or less the same in the Early Cretaceous. Such low δ18O meteoric water (< −17‰) is seen in high-latitude regions, i.e., modern meteoric precipitation of the Greenland ranges from −15‰ to −35‰35. These kinds of regions usually have very low precipitation. Given that Baerzhe is located several thousand kilometers away from such low δ18O region, with higher precipitation and much higher δ18O, it is not likely that water from high latitudes can be transported to Baerzhe through rivers and keeps the very low δ18O values. Glacier is the only plausible way that transports water for thousands of kilometers and keep the extremely low δ18O values. Therefore, continental glacial meltwater is the most likely source for the negative δ18O water (−17‰ to −34‰), responsible for the 18O-depleted Baerzhe hydrothermal zircon at mid-latitudes27. The occurrence of glacier meltwater incorporated in the hydrothermal zircon can be interpreted to imply mean annual temperatures of < −7.5°C in the target region (Fig. 4).

The mean annual temperature (MAT, °C) can be estimated from the δ18O values (‰, VSMOW) of hydrothermal fluid that yielded the hydrothermal zircon.

If the hydrothermal fluid was composed of different proportions of surface water (from 90% to 10%) and magmatic water, the estimated mean annual temperature of lower than −7.5 °C, using the following equation: δ18O = 0.64 × T (°C) − 12.8 56.

In principle, glacial meltwater may be incorporated into hydrothermal zircon either by direct mixing with magmatic fluid, or by assimilation of supracrustal rocks that have previously been altered by the glacial meltwater at high temperatures. The latter requires interaction between glacial meltwater and granitic magma during the emplacement, imparting the extremely negative δ18O values to cooling magmas to generate the similar δ18O values of hydrothermal fluid. Although the O isotopes of hydrothermal zircon are controlled by both magmatic water and glacial meltwater, the budget for water-insoluble trace elements in zircon is dominated by the granitic melts. In contrast to the dramatic difference in O isotopes between the hydrothermal and magmatic zircon, Hf isotopes of hydrothermal zircon fall within the range of those of magmatic zircon (Fig. 3). This suggests that the hydrothermal zircon gained extremely negative δ18O without significant changes in Hf isotope composition, which does not favor the assimilation of supracrustal rocks during magma emplacement. The whole rock Hf-Nd isotopes analyses also suggest that the Baerzhe granitic magma was derived from partial melting of juvenile crust, without significantly supracrustal assimilation (Supplementary Fig. S5). Therefore, extremely low δ18O water participated in shallow intrusions24,36 is the favorable explanation for Baerzhe hydrothermal zircon.

The occurrence of continental glacial meltwater indicates the presence of an exceptionally cold paleoclimate locally in northeastern Asia in the early Aptian. This is supported by global sea-level changes, carbon isotopes in oceanic sediments and some paleontological data from Jehol Biota. Sea-level records from 100 to 155 Ma suggest a warm global climate during the Earliest Cretaceous, followed by dramatic sea-level falls, which was attributed to glacioeustasy from the late Barremian (ca. 128.3 Ma) to the early Aptian (ca. 123.3 Ma)6,37. In addition, there is a major negative shift of carbon isotopes for the Pacific carbonate section at ~ 124 Ma38, indicating abrupt methane emission that may have been triggered by oceanic deglaciation39. All these suggest that the continental ice sheet may have developed locally in northeastern Asia and supplied deglacial meltwater to mid-paleolatitude regions (~45°N) in the early Aptian.

Consistently, cool paleoclimate is supported by paleontological evidence, including plant fossils such as fossil wood genus Xenoxylon40, insect fossils such as stoneflies and raphidiopterans41 and the absence of thermophilic reptiles such as crocodilians8. Most significantly, the recent discovery of a gigantic feathered theropod dinosaur with long feathers in the Early Cretaceous from Jehol Biota was proposed to be analogous to some large mammal taxa, e.g. mammuthus primigenius, in ice age, in terms of developing long integumentary coverings as an adaptation to an unusually cold environment42.

Previous studies demonstrate the presence of cold intervals during the greenhouse Mesozoic5,6,37, but the documentation of continental glaciation in mid-latitude regions is somewhat unexpected. The Jehol Biota lasted for about 10 million years, whereas it is likely that this early Aptian ice age represents only a short-lived cold interval during existence of the Jehol Biota. Our study thus encourages more high-resolution geochemical and other studies which may reveal more cold intervals during the Mesozoic greenhouse era. The exceptionally cold climate in the Early Cretaceous in northeastern Asia is also inconsistent with abundant evidence supporting a much warmer climate in low-latitude regions1,4,5,43. This can be explained by the hypothesis that the climate regime of the Earth during the Mesozoic is different from the present, i.e., a much steeper pole-to-equator temperature gradient in the Mesozoic than today5.

The increasing evidence supporting large temperature fluctuations during the greenhouse Cretaceous has implications for our understanding of the evolution of the Mesozoic ecosystem. There is some evidence supporting the wide distribution of feathery or fury coverings in dinosaurs, pterosaurs and mammals, the three dominant Mesozoic groups44,45. The relative development of these integumentary coverings is possible to be linked with the tremendous temperature fluctuations, though the available data is far from enough yet to make such an inference.

In conclusion, the extremely low δ18O values for the hydrothermal zircon presented in this study favor an explanation by the incorporation of continental glacial meltwater rather than intracontinental water or the assimilation of previously altered rocks. The required glacial meltwater (−17‰ to −34‰) was corresponding to mean annual temperature of lower than −7.5°C, suggesting that continental ice sheet would had developed to the mid-latitude and low-altitude regions in NE Asia in the Early Cretaceous. This is a surprising result, because the Cretaceous is known to be one of the hottest periods in the Earth's history. More broadly, such extremely cold climates in the supergreenhouse Early Cretaceous might have brought significantly forces on the evolution of the Mesozoic ecosystem, including the Jehol Biota.

Methods

Zircon grains were separated using the standard density and magnetic separation techniques. Both hydrothermal and magmatic zircon grains were selected from mineralized and barren Baerzhe alkaline granites. These grains were handpicked under a binocular microscope and mounted in an epoxy resin disc, then polished to near half section to expose internal structures. Transmitted and reflected-light microscopy, CL and scanning electronic microscope (SEM) investigations were carried out before in-situ U-Pb dating and O-Hf isotopic analyses on inclusion-free domains.

SIMS U-Pb dating

U-Pb dating was conducted using a Cameca secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS) 1280 at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Science (IGGCAS) (Supplementary Table S2). Analytical procedures are the same as those described by Li et al.46. The O2− primary ion beam was accelerated at 13 kV, with an intensity of ca. 8 nA. The ellipsoidal spot is about 20 × 30 μm in size. Positive secondary ions were extracted with a 10 kV potential. The Pb/U calibration was performed using TEM zircon standard with an age of 417 Ma47. Data processing was carried out using the Isoplot 4.11 programs of Ludwig48 and the 204Pb-based method of common Pb correction was applied. The uncertainties in single analyses are cited as 1σ and the weighted mean ages are quoted at the 95% confidence level (2σ).

SIMS O isotopes analyses

The oxygen isotopic compositions of zircon were measured using the same Cameca IMS-1280 SIMS at the IGGCAS (Supplementary Table S3), with analytical procedures similar to those reported by Li et al.49. The Cs+ primary ion beam was accelerated at 10 kV, with an intensity of ca. 2 nA (Gaussian mode with a primary beam aperture of 200 μm to reduce aberrations) and rastered over a 10 μm area. The spot is about 20 μm in diameter (10 μm beam diameter + 10 μm raster). The normal incidence electron flood gun was used to compensate for sample charging. Negative secondary ions were extracted with a −10 kV potential. Oxygen isotopes were measured in multi-collector mode using two off-axis Faraday cups. The mass resolution used to measure oxygen isotopes was ca. 2500. The nuclear magnetic resonance probe was used for magnetic field control with stability better than 2.5 ppm over 16 hours on mass 17. The instrumental mass fractionation factor (IMF) is corrected using zircon 91500 standard with a δ18O value of 9.86 ± 0.11‰50. Penglai zircon megacrysts with a reference δ18O value of 5.31 ± 0.10‰ were used for further external adjustments51 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Measured 18O/16O ratios were normalized by using Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water compositions (VSMOW, 18O/16O = 0.0020052) and then corrected for the instrumental mass fractionation factor (IMF) as follows: (δ18Ο)M = [(18O/16O)M/0.0020052-1] × 1000 (‰), IMF = (δ18O)M(standard) – (δ18O)VSMOW, δ18OSample = (δ18O)M + IMF.

LA-MC-ICPMS Hf isotopes analyses

Hf-isotope analyses were carried out in-situ using a Nu Plasma HR MC-ICP-MS with a GeoLas 2005 excimer ArF laser-ablation system, at the State Key Laboratory of Continental Dynamics, Northwest University, Xi'an, China. The Nu Plasma HR MC-ICP-MS is a second-generation double-focusing MC-ICP-MS with three ion counters and twelve faraday cups. The GeoLas 2005 laser-ablation system consists of a COMPexPro 102 ArF excimer laser (wavelength of 193 nm, maximum energy of 200 mJ and maximum pulse rate of 20 Hz) and a GeoLas 2005 PLUS package. Lu-Hf isotopic analyses were obtained on the same zircon grains that were previously analyzed for O isotopes, with ablation pits of 44 μm in diameter, ablation time of 26 seconds, repetition rate of 7 Hz and laser beam energy density of 15 J/cm2. The analytical procedures were similar to those described by Yuan et al.52. Zircon 91500, Monastery and GJ-1 were used as external standards in this analysis and our 176Hf/177Hf ratios for the three zircon standards (Supplementary Fig. S4) are in good agreement with reported values52. Hf isotopic data for the hydrothermal and magmatic zircon are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Estimation of mean annual temperatures

Oxygen isotope ratios provide a powerful tool for understanding the thermal, magmatic and fluid history53,54. Yuan and Zhang55 reported δ18O values for whole rock and quartz, K-feldspar, zircon and albite from the Baerzhe granite (Table S3, Fig. S6). The highly negative δ18O values for whole-rock, K-feldspar and zircon suggest O isotopic disequilibrium between minerals in the granite. The huge Δ18OQuartz–K-feldspar values show that meteoric water has interacted with the granite (Supplementary Fig. S7).

The weighted average value of the 34 δ18O analyses for the magmatic zircon (excluding three mixed spots) is 3.47‰ ± 0.49‰ (1σ), which is significantly lower than the δ18O range of 5.3‰ ± 0.3‰ for zircon in high-temperature equilibrium with the normal mantle19. The statistical mean value of the 10 quartz δ18O analyses is 5.37 ± 0.54‰ (1σ). According to the theoretical calculations of O isotope fractionation20, equilibrium O isotope fractionations between quartz and magmatic zircon are 1.90 ± 0.73‰ (1σ) at magmatic temperatures. From the following fractionation equation20:

At equilibrium 103lnαquartz-zircon ≈ Δ18Oquartz-zircon ≈ δ18Oquartz – δ18Ozircon, we can estimate an equilibrium temperature (T) of ca. 1030°C (Supplementary Fig. S8). This temperature is only slightly higher than the homogenization temperature of 750–1030°C from primary melt inclusions in quartz phenocrysts12.

The minimum δ18O value of 31 hydrothermal zircon grains is −18.12 ± 1.5‰, which, from the theoretical calculations of zircon-water fractionation20, indicates hydrothermal fluid with a maximum δ18O value of −15.23‰. The equilibrium temperature was assumed at 600°C, which consistent with the homogenization temperatures of 475 to 650°C from melt-fluid inclusions in the pegmatite of the Baerzhe deposit12.

At equilibrium 103lnαzircon-water ≈ Δ18Ozircon-water ≈ δ18Ozircon – δ18Owater. If T = 600°C, 103 lnαzircon-water = −2.89‰. Using these values, we obtain the δ18O value of −15.23‰ for the hydrothermal fluid. Whereas, the hydrothermal fluid that yielded the hydrothermal zircons should be composed of surface water (SW) and magmatic water (MW). The A-type granite normally is anhydrous, which means that only a limited amount of magmatic fluid was exsolved from the Baerzhe magma. Assuming that the proportion of incorporated surface water (w1) is ≤ 90% and the primary magmatic water is (w2) is ≥ 10%, the δ18O value of the hydrothermal fluid is calculated as:

where, w1 + w2 = 1.

The relationship between δ18O value of continental surface water and annual temperature (T, °C)56 is as follows:

Furthermore, the magmatic fluid exsolved from the Baerzhe magma should be in O isotopic equilibrium with the magmatic zircon. From the theoretical calculations of zircon-water20, we obtain a δ18OMW value of 6.36 ± 0.52% for the magmatic water at 600°C.

We can now estimate the mean annual temperature using the δ18O value of the hydrothermal fluid, as show in Fig. 4.

It is possible that the incorporation of surface water at the magmatic-hydrothermal transition (ca. 600°C), varied in different parts of the pluton. Assuming the lowest measured δ18O value of −18.12 ± 1.5‰ in the hydrothermal zircon is composed of 90% surface water in the hydrothermal fluid, the corresponding mean annual temperature is ca. −7.5°C. The range of δ18O values of the hydrothermal zircon (−18.12 ± 0.15‰ to −13.19 ± 0.14‰) could be due to variably amounts of surface water (continental glacial meltwater).

References

Herman, A. B. & Spicer, R. A. Palaeobotanical evidence for a warm Cretaceous Arctic Ocean. Nature 380, 330–333 (1996).

Huber, B. T., Norris, R. D. & MacLeod, K. G. Deep-sea paleotemperature record of extreme warmth during the Cretaceous. Geology 30, 123–126 (2002).

Miller, K. G. et al. The phanerozoic record of global sea-level change. Science 310, 1293–1298 (2005).

Littler, K., Robinson, S. A., Bown, P. R., Nederbragt, A. J. & Pancost, R. D. High sea-surface temperatures during the Early Cretaceous Epoch. Nat. Geosci. 4, 169–172 (2011).

Price, G. D. The evidence and implications of polar ice during the Mesozoic. Earth-Sci. Rev. 48, 183–210 (1999).

Mutterlose, J. & Malkoc, M. The Early Barremian warm pulse and the Late Barremian cooling: A high-resolution geochemical record of the boreal realm. Palaios 25, 14–23 (2010).

Puceat, E. et al. Thermal evolution of Cretaceous Tethyan marine waters inferred from oxygen isotope composition of fish tooth enamels. Paleoceanography 18, 1029 (2003).

Amiot, R. et al. Oxygen isotopes of East Asian dinosaurs reveal exceptionally cold Early Cretaceous climates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5179–5183 (2011).

Jahn, B. M. et al. Highly evolved juvenile granites with tetrad REE patterns: the Woduhe and Baerzhe granites from the Great Xing'an Mountains in NE China. Lithos 59, 171–198 (2001).

Niu, H. C., Shan, Q., Luo, Y., Yang, W. B. & Yu, X. Y. Study on the crystal-rich fluid inclusions from the Baerzhe super-large rare elements and REE deposit. Acta Petrologica Sinica 24, 2149–2154 (2008) (in Chinese with English abstract).

Yang, W. B., Niu, H. C., Shan, Q., Luo, Y. & Yu, X. Y. Ore-forming mechanism of the Baerzhe super-large rare and rare earth elements deposit. Acta Petrologica Sinica 25, 2924–2932 (2009) (in Chinese with English abstract).

Yang, W. B. et al. Melt and melt-fluid inclusions in the Baerzhe alkaline granite: Information of the magmatic-hydrothermal transition. Acta Petrologica Sinica 27, 1493–1499 (2011) (in Chinese with English abstract).

Bumham, C. W. & Ohmoto, H. Late-stage processes of felsic magmatism. Mining Geology Special Issue 8, 1–11 (1980).

Audetat, A. & Pettke, T. The magmatic-hydrothermal evolution of two barren granites: A melt and fluid inclusion study of the Rito del Medio and Canada Pinabete plutons in northern New Mexico (USA). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 97–121 (2003).

Pupin, J. P. Zircon and granite petrology. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 73, 207–220 (1980).

Belousova, E. A., Griffin, W. L. & O'Reilly, S. Y. Zircon crystal morphology, trace element signatures and Hf isotope composition as a tool for petrogenetic modelling: Examples from Eastern Australian granitoids. J. Petrol. 47, 329–353 (2006).

Gasquet, D. et al. Hydrothermal zircons: A tool for ion microprobe U-Pb dating of gold mineralization (Tamlalt-Menhouhou gold deposit Morocco). Chem. Geol. 245, 135–161 (2007).

Hoskin, P. W. O. Trace-element composition of hydrothermal zircon and the alteration of Hadean zircon from the Jack Hills, Australia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 637–648 (2005).

Valley, J. W., Kinny, P. D., Schulze, D. J. & Spicuzza, M. J. Zircon megacrysts from kimberlite: oxygen isotope variability among mantle melts. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 133, 1–11 (1998).

Zheng, Y. F. Calculation of oxygen isotope fractionation in anhydrous silicate minerals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 1079–1091 (1993).

Wei, C. S., Zheng, Y. F., Zhao, S. F. & Valley, J. W. Oxygen isotope evidence for two-stage water-rock interactions of the Nianzishan A-type granite in NE China. Chinese Sci. Bull. 46, 727–731 (2001).

Wei, C. S., Zheng, Y. F., Zhao, Z. F. & Valley, J. W. Oxygen and neodymium isotope evidence for recycling of juvenile crust in northeast China. Geology 30, 375–378 (2002).

Valley, J. W. Oxygen isotopes in zircon. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 53, 343–385 (2003).

Bindeman, I. N., Brooks, C. K., McBirney, A. R. & Taylor, H. P. The low-delta(18)O late-stage ferrodiorite magmas in the skaergaard intrusion: Result of liquid immiscibility, thermal metamorphism, or meteoric water incorporation into magma? J. Geol. 116, 571–586 (2008).

Zheng, Y. F. et al. Zircon U-Pb and oxygen isotope evidence for a large-scale O-18 depletion event in igneous rocks during the neoproterozoic. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 4145–4165 (2004).

Zheng, Y. F., Gong, B., Zhao, Z. F., Wu, Y. B. & Chen, F. K. Zircon U-Pb age and O isotope evidence for Neoproterozoic low-O-18 magmatism during supercontinental rifting in South China: Implications for the snowball Earth event. American J. Sci. 308, 484–516 (2008).

Zheng, Y. F. et al. Tectonic driving of Neoproterozoic glaciations: Evidence from extreme oxygen isotope signature of meteoric water in granite. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 256, 196–210 (2007).

Tang, J. et al. Extreme oxygen isotope signature of meteoric water in magmatic zircon from metagranite in the Sulu orogen, China: Implications for Neoproterozoic rift magmatism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 3139–3169 (2008).

Watson, E. B. & Cherniak, D. J. Oxygen diffusion in zircon. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 148, 527–544 (1997).

Zheng, Y. F. & Fu, B. Estimation of oxygen diffusivity from anion porosity in minerals. Geochem. J. 32, 71–89 (1998).

Bindeman, I. N., Schmitt, A. K. & Evans, D. A. D. Limits of hydrosphere-lithosphere interaction: Origin of the lowest-known delta(18)O silicate rock on Earth in the Paleoproterozoic Karelian rift. Geology 38, 631–634 (2010).

Enkin, R. J., Yang, Z. Y., Chen, Y. & Courtillot, V. Paleomagnetic Constraints on the Geodynamic History of the Major Blocks of China from the Permian to the Present. J Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 97, 13953–13989 (1992).

Shao, J. A., Zhao, G. L., Wang, Z. & Han, Q. J. Tectonic setting of Mesozoic volcanism in Da Hinggan Mountains, northeastern China. Geological Review 45, 422–430 (1999) (in Chinese with English abstract).

King, P. & White, A. in the Ishihara symposium: Granites and Associated metallogenesis, Geoscience Australia. 85–88 (2004).

Bowen, G. J. & Wilkinson, B. Spatial distribution of delta O-18 in meteoric precipitation. Geology 30, 315–318 (2002).

D'Errico, M. E. et al. A detailed record of shallow hydrothermal fluid flow in the Sierra Nevada magmatic arc from low-delta O-18 skarn garnets. Geology 40, 763–766 (2012).

Sahagian, D., Pinous, O., Olferiev, A. & Zakharov, V. Eustatic curve for the Middle Jurassic-Cretaceous based on Russian platform and Siberian stratigraphy: Zonal resolution. Aapg. Bull. 80, 1433–1458 (1996).

Jenkyns, H. C. Geochemistry of oceanic anoxic events. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11 (2010).

Yu, J. B. et al. Enhanced net formations of nitrous oxide and methane underneath the frozen soil in Sanjiang wetland, northeastern China. J Geophys. Res.-Atmospheres 112, D07111 (2007).

Philippe, M. & Thevenard, F. Distribution and palaeoecology of the Mesozoic wood genus Xenoxylon: palaeoclimatological implications for the Jurassic of Western Europe. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 91, 353–370 (1996).

Liu, Y. S., Ren, D., Sinitshenkova, N. D. & Shih, C. K. Three new stoneflies (Insecta: Plecoptera) from the Yixian Formation of Liaoning, China. Acta Geologica Sinica 82, 249–256 (2008).

Xu, X. et al. A gigantic feathered dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China. Nature 484, 92–95 (2012).

Larson, R. L. & Erba, E. Onset of the mid-Cretaceous greenhouse in the Barremian-Aptian: Igneous events and the biological, sedimentary and geochemical responses. Paleoceanography 14, 663–678 (1999).

Zheng, X. T., You, H. L., Xu, X. & Dong, Z. M. An Early Cretaceous heterodontosaurid dinosaur with filamentous integumentary structures. Nature 458, 333–336 (2009).

Xu, X., Zheng, X. T. & You, H. L. A new feather type in a nonavian theropod and the early evolution of feathers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 832–834 (2009).

Li, X. H., Liu, Y., Li, Q. L., Guo, C. H. & Chamberlain, K. R. Precise determination of Phanerozoic zircon Pb/Pb age by multicollector SIMS without external standardization. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10, 1525–2027 (2009).

Black, L. P. et al. Improved (206)Pb/(238)U microprobe geochronology by the monitoring of a trace-element-related matrix effect; SHRIMP, ID-TIMS, ELA-ICP-MS and oxygen isotope documentation for a series of zircon standards. Chem. Geol. 205, 115–140 (2004).

Ludwig, K. R. User's manual for Isoplot, v. 3.0: A geochronological toolkit for Microsoft Excel. Berkeley Geochronological Center, Spec. Pub. No. 4 (2003).

Li, X. H. et al. Petrogenesis and tectonic significance of the similar to 850 Ma Gangbian alkaline complex in South China: Evidence from in situ zircon U-Pb dating, Hf-O isotopes and whole-rock geochemistry. Lithos 114, 1–15 (2010).

Wiedenbeck, M. et al. Further characterisation of the 91500 zircon crystal. Geostands Geoanalytical Res. 28, 9–39 (2004).

Li, X. H. et al. Penglai Zircon Megacrysts: A Potential New Working Reference Material for Microbeam Determination of Hf-O Isotopes and U-Pb Age. Geostands Geoanalytical Res. 34, 117–134 (2010).

Yuan, H. L. et al. Simultaneous determinations of U-Pb age, Hf isotopes and trace element compositions of zircon by excimer laser-ablation quadrupole and multiple-collector ICP-MS. Chem. Geol. 247, 100–118 (2008).

Valley, J. W., Chiarenzelli, J. R. & Mclelland, J. M. Oxygen-Isotope Geochemistry of Zircon. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 126, 187–206 (1994).

Hoefs, J. Stable isotope geochemistry. 6th Edition, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, 284 (2009).

Yuan, Z. X., Zhang, M. & Wan, D. F. A discussion on the petrogenesis of 18O-low alkali granite: A case study of Baerzhe alkali granite in Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrologica et Mineralogica 22, 119–124 (2003) (in Chinese with English abstract).

Jouzel, J., Koster, R. D., Suozzo, R. J. & Russell, G. L. Stable water isotope behavior during the last glacial maximum: A general circulation model analysis. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmospheres 99, 25791–25801 (1994).

Zhou, Z. H., Barrett, P. M. & Hilton, J. An exceptionally preserved Lower Cretaceous ecosystem. Nature 421, 807–814 (2003).

Chang, S. C., Zhang, H. C., Renne, P. R. & Fang, Y. High-precision (40)Ar/(39)Ar age for the Jehol Biota. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 280, 94–104 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Professors Xianhua Li and Qiuli Li for their help with SIMS zircon U-Pb dating and O isotopes analyses, Dr. Hong Zhang for MC-ICPMS zircon Lu-Hf isotope analyses, Profs. Ian S. Williams and Fanrong Chen for useful discussions and English polishing during manuscript preparation. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (40872066, 41121002) and GIGCAS 135 project Y234041001. This is contribution No. IS-1715 from GIGCAS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.C.N. and W.D.S. designed the project. W.B.Y., W.D.S., H.C.N., Y.F.Z., X.X. and N.T.A. wrote the main manuscript text and W.B.Y. and H.C.N. prepared the figures. W.B.Y., H.C.N. and X.Y.Y. identified, located and prepared the sample for analysis. Q.S., W.B.Y., C.Y.L., N.B.L. and Y.H.J. performed U-Pb dating, oxygen and hafnium isotopes measurements. All authors participated in the discussion and commented on the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, WB., Niu, HC., Sun, WD. et al. Isotopic evidence for continental ice sheet in mid-latitude region in the supergreenhouse Early Cretaceous. Sci Rep 3, 2732 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02732

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02732

This article is cited by

-

Permafrost in the Cretaceous supergreenhouse

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Origin of the Low δ18O Signals in Zircons from the Early Cretaceous A-Type Granites in Eastern China: Evidence from the Kulongshan Pluton

Journal of Earth Science (2021)

-

Study on the Jehol Biota: Recent advances and future prospects

Science China Earth Sciences (2020)

-

Geochemistry of magmatic and hydrothermal zircon from the highly evolved Baerzhe alkaline granite: implications for Zr–REE–Nb mineralization

Mineralium Deposita (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.