Abstract

The Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) experiment was a benchmark in quantum optics, evidencing the non–classical nature of photon pairs, later generalized to quantum systems with either bosonic or fermionic statistics. We show that a simple modification in the well-known and widely used HOM experiment provides the direct measurement of the Wigner function. We apply our results to one of the most reliable quantum systems, consisting of biphotons generated by parametric down conversion. A consequence of our results is that a negative value of the Wigner function is a sufficient condition for non-gaussian entanglement between two photons. In the general case, the Wigner function provides all the required information to infer entanglement using well known necessary and sufficient criteria. The present work offers a new vision of the HOM experiment that further develops its possibilities to realize fundamental tests of quantum mechanics using simple optical set-ups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Entangled photon pairs play undoubtedly a central role in quantum information processing and quantum communication. Photons are the most efficient quantum information carriers, not only for their intrinsic propagation speed, but also for the variety of degrees of freedom they possess, both discrete and continuous. Some examples of quantum information protocols that have been realized with photons are teleportation1, quantum key distribution2, one–way quantum computing3 and quantum repeaters4. Moreover, entangled photon pairs enable the realization of fundamental tests of quantum mechanics, as Bell type inequalities5,6, since the no–signalling condition is relatively easily fulfilled.

Spontaneous parametric down conversion (SPDC) is the most widely used process to generate entanglement in different (independent) degrees of freedom of a photon pair. Detecting, characterizing and manipulating this entanglement is a key issue for quantum information applications. This problem is fundamentally different if one is dealing with discrete degrees of freedom (e.g. polarization), or with continuous ones (e.g. spatial or spectral). While for two qubit states in the discrete case and for gaussian states in the continuous one, necessary and sufficient conditions exist for entanglement detection7,8, for higher dimensions or more general configurations, solutions are subspace dependent9. However, using high dimensional systems and non Gaussian states leads to a number of important and interesting applications, such as entanglement distillation10, quantum computation11 and high precision measurement12. For these reasons, understanding and classifying such states is a matter of importance and fundamental interest.

Photons produced by SPDC can be highly non-separable because the characteristics of the pump beam and of the nonlinear medium are transferred to global degrees of freedom of the photon pair. This transfer also occurs in the strong field regime where the quadratures of the down converted fields are entangled and could present non Gaussian behaviour for sufficiently high nonlinear coupling13. In the photon pair regime, we often speak of biphoton states. For instance, using a continuous wave (cw) pump and considering degenerate, monochromatic and polarized fields, the two-photon state can be written as14,15

where F+ is the normalized momentum distribution of the pump beam, F− is the phase matching function and pi the Transverse Momentum (TM) vector of the i-th photon15. Eq. (1) can indeed be obtained for several types of continuous variables (namely spatial or frequency coordinates) and in a wide range of experimental setups, as we will show below. We denote p± = p1 ± p2 and q± = q1 ± q2 (the sum and differences of position coordinates). The correlations of the biphoton are determined by the functions F±(p±) and their Fourier transforms  , which describe the photons in the transverse position coordinate. To gain information about the entanglement in state (1), measurement of the coincidence distributions in at least Fourier conjugate planes is required. Furthermore, to gain total information about the quantum state through tomography requires measurement of correlations along additional directions in the phase space of the transverse spatial variables16. This could be done, in principle, by generalizing the method demonstrated in17 where the Wigner function18 of a single photon was directly measured using a Sagnac interferometer. This method can, in principle, lead to the measurement of the Wigner function for photons prepared in an arbitrary state, but it demands the stabilization of independent interferometers. The method to measure the biphoton's Wigner function presented here, as will be seen in the following has a much higher stability in spite of the symmetry conditions required for the wave-function. Moreover, it is based on a currently used technique to probe the quantum statistical properties of bosons and fermions. It is obvious from Eq. (1) that all of the information about correlations between photons 1 and 2 can be obtained through measurements on the sum and difference variables, p±.

, which describe the photons in the transverse position coordinate. To gain information about the entanglement in state (1), measurement of the coincidence distributions in at least Fourier conjugate planes is required. Furthermore, to gain total information about the quantum state through tomography requires measurement of correlations along additional directions in the phase space of the transverse spatial variables16. This could be done, in principle, by generalizing the method demonstrated in17 where the Wigner function18 of a single photon was directly measured using a Sagnac interferometer. This method can, in principle, lead to the measurement of the Wigner function for photons prepared in an arbitrary state, but it demands the stabilization of independent interferometers. The method to measure the biphoton's Wigner function presented here, as will be seen in the following has a much higher stability in spite of the symmetry conditions required for the wave-function. Moreover, it is based on a currently used technique to probe the quantum statistical properties of bosons and fermions. It is obvious from Eq. (1) that all of the information about correlations between photons 1 and 2 can be obtained through measurements on the sum and difference variables, p±.

In the present paper, we show that the biphoton Wigner function can be measured directly using an adaptation of the Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) interferometer19. In the following, we detail how to detect the biphoton Wigner distribution in the whole phase space and consequently, obtain a full characterization of the two-photon quantum state, by using readily available linear optics elements. Furthermore, we show that HOM interference can be used as an entanglement witness for non-Gaussian entanglement. Negative values of the biphoton Wigner function is a sufficient condition to prove the presence of non-Gaussian entanglement in the system.

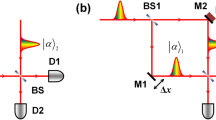

Let us first recall the principles of the HOM interferometer, shown in Fig. 1. Each photon of a pair created from SPDC is sent through one of the two arms of an interferometer. They are then recombined in a 50/50 beam splitter (BS) and detected by detectors A and/or B. When the photons are indistinguishable and reach the BS simultaneously, they bunch and follow the same path. Coincidence detections in detectors in A and B are thus less likely and the so-called “Hong-Ou-Mandel dip” is observed19.

For notational simplicity, we write the state of a continuous variable degree of freedom of the photons as |Ψ〉 = ∫ ∫ F(p1, p2)|p1, p2〉dp1dp2, where pi are variables associated to the i-th photon (i = 1, 2) that propagates in the i-th arm of the interferometer. We impose that all other degrees of freedom are separable from the considered one, which can be guaranteed using filters to make local projections. In order to better illustrate the main idea, we will first take pi as being the TM of the i-th photon produced in the SPDC process and consider only one spatial dimension15. This direction will be such that it is not modified by mirror reflection. It will be called y later on. Examples of applications to other continuous degrees of freedom and extension to two dimensions will be given below.

Results

In the present version of the HOM experiment, we suppose the interferometer is calibrated and both photons reach the BS simultaneously. We then add a position translation 2δ to photon labeled 2 and a momentum translation μ to photon labeled 1. These operations are currently done using linear optical elements20 (see also Supplemental Material). After both position and momentum displacements, the biphoton state, impinging in the BS is:

After the BS, the two-photon state is given by

We will now focus on the coincidence detections only, i.e., consider only states corresponding to two photons exiting in different paths, A and B. The coincidence probability I(μ, δ) thus reads

Let us already note that separability of the biphoton wavefunction F(p1, p2) = f1(p1)f2(p2) implies I(μ, δ) ≤ 1/2. This applies to two-photon mixed states as well, since they can be constructed as a convex sum of separable pure states (see Supplemental Material). Thus I(μ, δ) ≤ 1/2 is an entanglement witness for general two-photon state of the TM. A similar result was obtained for other degrees of freedom in Refs. 21,22,23,24.

Let us now turn to the main result of our paper. For the sake of simplicity, we will independently discuss each transverse axis: y was previously defined and x is orthogonal to y. This is necessary since there is a fundamental difference between x and y axes under reflection upon a vertical mirror since px → −px and py → py. As a matter of fact, because of this reflection asymmetry, Eq. (4) corresponds to the coincidence counts when coordinate y is considered. As will be seen below, taking into account the reflection asymmetry of coordinate x slightly modifies the expression of the coincidence counts.

We start by assuming, as in Eq. (1), F(p1,i, p2,i) = F−(p−,i)F+(p+,i), where i = x, y. This assumption is verified in most experiments with SPDC and is commonly used when studying entanglement in this process15,25. From now on, in order to simplify the notation, we will index functions instead of variables so that F+(p+,i) ≡ Fi+(p+), for instance.

The integral in Eq. (4) reads differently for x or y coordinates due to the aforementioned reflection asymmetry. For the y axis, we have

while for the x axis we have

First, let us notice that normalization can be chosen so that the first integrals in Eqs. (5) and (6) are unity (integrals in p+ and p−, respectively). Eq. (5) becomes

while Eq. (6) becomes:

where Wy−(μ, δ) and Wx+(μ, δ) are, by definition, the Wigner functions at point (μ, δ)18 associated to wave functions Fy− or Fx+, respectively.

Thus, the coincidence probability in this adapted version of the HOM experiment reveals the Wigner function at phase space point (μ, δ):

where j = x+ or j = y−. We stress that, in the case where space components are not separable and/or the wavefunction is not separable in the “+” and “−” coordinates, our main result still holds: the proposed adaptation of the HOM experiment leads to the Wigner function of the biphoton. Except that in this case, we experimentally access specific regions of the phase space. Also, it is a straightforward calculation to show that the Wigner function of a non-pure state can also be directly measured using the HOM set-up described above (see Supplemental Material).

From the Wigner function one can infer all the necessary information about the state and in particular, entanglement for Gaussian and non-Gaussian states. The witness defined by I(μ, δ) ≤ 1/2 allows to detect non-Gaussian states since they may have negative values of the Wigner function. Though the witness itself does not detect gaussian entanglement, we can nevertheless use the Wigner function to test Gaussian entanglement using other criteria7,8. These facts, added to the one that no assumption is being made on the width of the distribution, are clear advantages of the present method over discretization based techniques for detecting entanglement in continuous variable systems25.

We note that the Wigner function appearing in (7) is a single-party Wigner function referring to the sum or difference coordinates of the biphoton. This is a direct consequence of the form of state (1) and momentum conservation. The four dimensional phase space associated to a two particle system is mapped to a product of two dimensional spaces, each corresponding to collective variables p± and q±.

We have shown that the reflexion asymmetry of the TM correlates the measurement of the entanglement properties of F+ or F− to orthogonal traverse directions (Eqs. (7) and (8)). However, one can measure these functions in either axis, since they can be controllably interchanged, for instance by adding a Dove prism orientated at 45° in both arms of the HOM interferometer that rotates the fields by 90°.

Up to now, we have independently considered each degree of freedom of the biphoton, but the spatial variables are inherently two-dimensional (2D), as exemplified by Eq. (1). This leads to a four-dimensional Wigner function, instead of a two-dimensional one. Using the obtained results and considering the reflection properties of the BS, it is straightforward to show that the four-dimensional Wigner function returns information about F+ in the x direction and about F− in the y direction. If we consider, for instance, a two-photon state of the form (1), in the approximation where both transverse coordinates are separable, the application of our results to the two dimensions simultaneously, gives

Using Dove prisms can lead to similar expressions as (10) involving orthogonal coordinates, as mentioned above. It is also worth mentioning that even if transverse coordinates are not separable, I(μx, δx; μy, δy) reveals the Wigner function of each transverse coordinate. In this case, we are measuring the Wigner function of non pure states, as detailed in the Supplemental Material.

We now illustrate our results by studying in more details some examples. Let us first consider entanglement in TM naturally produced in cw SPDC using a gaussian pump. In this case, we have, in (5), that  and

and  , where wp is the width of the pumping beam momentum distribution, k is the wave number of the pumping beam and L is the non linear medium's length. For simplifying reasons, we will only study coordinate y. This can be done by fixing μx and δx in x and scanning only the y phase space, i.e., varying μy and δy only. Thus, πWx+(μx, δx) is a multiplicative constant. In the studied example, since the pump is gaussian, this constant is necessarily positive and can be set to 1 by a proper choice of μx, δx and the width of the pump. Thus, Eq. (10) directly provides Wy−(μy, δy). Supposing, for simplicity, that spatial coordinates are separable, we can apply Eq. (5) to compute it, with

, where wp is the width of the pumping beam momentum distribution, k is the wave number of the pumping beam and L is the non linear medium's length. For simplifying reasons, we will only study coordinate y. This can be done by fixing μx and δx in x and scanning only the y phase space, i.e., varying μy and δy only. Thus, πWx+(μx, δx) is a multiplicative constant. In the studied example, since the pump is gaussian, this constant is necessarily positive and can be set to 1 by a proper choice of μx, δx and the width of the pump. Thus, Eq. (10) directly provides Wy−(μy, δy). Supposing, for simplicity, that spatial coordinates are separable, we can apply Eq. (5) to compute it, with  . Corresponding results are shown in Fig. (2a) and (2b), showing Wy−(μy, δy) and I(μy, δy). Using realistic parameters, we can have I(μy, δy) = 0.56 for δy ≈ 0.1 mm, which fits well in the width of the transverse position distribution of the photon pairs. The relative violation of the separability threshold is of over 10%. Usually, this function is approximated by a Gaussian and the relatively high violation of the entanglement witness shows the limitations of this approximation.

. Corresponding results are shown in Fig. (2a) and (2b), showing Wy−(μy, δy) and I(μy, δy). Using realistic parameters, we can have I(μy, δy) = 0.56 for δy ≈ 0.1 mm, which fits well in the width of the transverse position distribution of the photon pairs. The relative violation of the separability threshold is of over 10%. Usually, this function is approximated by a Gaussian and the relatively high violation of the entanglement witness shows the limitations of this approximation.

Wigner function (normalized to π) and region I(μi, δi) > 1/2 in some chosen variable (i = x, y, ω, τ) for three output wave functions of the bi-photon in the SPDC process.

Variables in all the plots are in units of the relevant physical parameters:  ,

,  , μω [cL−1(n1 − n2)−1] and δτ [c−1L(n1 − n2)]. (a) Output of a cw pumping creating entanglement in the transverse momentum (TM) distribution. Violation of about 12% can be obtained with displacements in the TM axis, as shown in (b). (c) and (d) Schrödinger cat state in the TM with

, μω [cL−1(n1 − n2)−1] and δτ [c−1L(n1 − n2)]. (a) Output of a cw pumping creating entanglement in the transverse momentum (TM) distribution. Violation of about 12% can be obtained with displacements in the TM axis, as shown in (b). (c) and (d) Schrödinger cat state in the TM with  . We see that a violation of over 0.9 is obtained. (e) and (f): Frequency entangled states produced in the SPDC process through pulsed pumping.

. We see that a violation of over 0.9 is obtained. (e) and (f): Frequency entangled states produced in the SPDC process through pulsed pumping.

Discussion

Our results can be further exploited by modifying the pumping configurations and measuring the biphoton Wigner function that depends on the pump profile, i.e., Wx+(μx, δx). We can, for instance, create Schrödinger cats26 in the TM space and directly probe their Wigner function. This can be done by coherently splitting the pumping beam in two and displacing one with respect to the other in momentum space, for instance with the help of Spatial Light Modulators (SLM). As a consequence, the TM distribution will be centered in two different points, which distance we denote by Δpp. The biphoton Wigner function in his case is as in Fig. (2c), where we considered  . The entangled biphoton is highly non-Gaussian and violates the proposed witness by over 80% (see Fig. (2d)). This configuration can also be useful to study the decoherence of entangled non-Gaussian states through the Wigner function27.

. The entangled biphoton is highly non-Gaussian and violates the proposed witness by over 80% (see Fig. (2d)). This configuration can also be useful to study the decoherence of entangled non-Gaussian states through the Wigner function27.

Let us remark that previous results, as in14 can now be re-interpreted with the present formulation. We see that in14, as in the usual HOM experiment, the Wigner function at point I(0, 0; 0, 0) was measured (see Supplemental Material for a revision of these results using the present formulation).

We provide now a second example of an experimental set-up where our results can be applied. It consists in SPDC generated from a pulsed pump in semi conductor waveguides28,29. In this case, pairs of photons entangled in frequency are created, so the space of CV is one dimensional only. The output wave function is such that  and

and  where ni are the refractive index of the medium for the i-th photon, L is the medium's length, ω± = ω1 ± ω2 where ωi is the i-th photon frequency. There is a complete analogy between these functions and the one dimensional TM case and the same reasoning can be applied leading to the measurement of the Wigner function. However, scanning the whole phase space in this case demands using optical elements leading to frequency displacements μω and frequency proportional dephasing δτ. Frequency displacements can be realized using techniques as the one demonstrated in30, while δτ displacements can be done either by time-delaying one arm of the interferometer or by using linear optics elements. Expected results with the considered functions are depicted in Figs. (2e), (2f)). In21, a state analogous to the Schrödinger cat in Fig. (2c), was created by pumping the medium with a Gaussian beam in a regime where two different phase matching conditions apply. A violation of less than 4% was observable using displacements in the δτ axis only by time delaying one photon(equivalent to displacements in δx in Figs. (2c), (2d)). Negative points were observed which we can now interpret as interference fringes of the Wigner function of a biphoton Schrödinger cat state (see Supplemental Material for further discussion).

where ni are the refractive index of the medium for the i-th photon, L is the medium's length, ω± = ω1 ± ω2 where ωi is the i-th photon frequency. There is a complete analogy between these functions and the one dimensional TM case and the same reasoning can be applied leading to the measurement of the Wigner function. However, scanning the whole phase space in this case demands using optical elements leading to frequency displacements μω and frequency proportional dephasing δτ. Frequency displacements can be realized using techniques as the one demonstrated in30, while δτ displacements can be done either by time-delaying one arm of the interferometer or by using linear optics elements. Expected results with the considered functions are depicted in Figs. (2e), (2f)). In21, a state analogous to the Schrödinger cat in Fig. (2c), was created by pumping the medium with a Gaussian beam in a regime where two different phase matching conditions apply. A violation of less than 4% was observable using displacements in the δτ axis only by time delaying one photon(equivalent to displacements in δx in Figs. (2c), (2d)). Negative points were observed which we can now interpret as interference fringes of the Wigner function of a biphoton Schrödinger cat state (see Supplemental Material for further discussion).

In conclusion, we have provided a new interpretation of the coincidence probability in the HOM experiment in terms of a biphoton Wigner function. We adapted the HOM set-up so as all the points of the Wigner function can be detected by using available linear optics elements. Negative points of the Wigner function are associated to non-Gaussian entanglement, that can be directly detected in this type of experiment. For Gaussian entanglement, the information provided by the Wigner function can also be used applying other entanglement criteria. We analyze previous experimental results using the new perspective provided by our formulation, that can be generalized to an arbitrary number of photons (see Supplemental Material) or to other quantum particles with either bosonic or fermionic statistics satisfying the conditions established in the present work31,32. Our results open the path to realizing new fundamental tests of quantum mechanics in a simple and currently used optical setup.

Methods

Calculation of the coincidence probability

In deriving equation 4, we used the following equality:

and performed straightforward changes of variables. The coincidence probability is thus simply the squared modulus of this integral.

Four dimensional Wigner function

The most general (pure) two–photon, two–dimensional wave function can be expressed as:

where pi± = p1,i ± p2,i with i = x, y. By repeating the same calculations developed in the main text and in (20), we have that the coincidences probability is:

Thus, in the general case,

The first pair of coordinates in the equation above refer to the part of the Wigner function that depends on the x, + variables and the second pair to the part of the Wigner function associated to the y, − coordinates. Notice that, by using Dove prisms, as suggested in the main text, one can change the significance of these variables: the first pair will be associated to the x, − function and the second one to the y, + one.

Interpretation of Eq. (14)

State (16) can be completely non–separable. In this case, we see from (5) that the Wigner function appearing in (14) reads:

where  is the reduced density matrix after the trace over variables

is the reduced density matrix after the trace over variables  and r⊥±, with r and r⊥ being two spacial orthogonal coordinates depending on the chosen reflection plane, that can be modified by using a Dove prism.

and r⊥±, with r and r⊥ being two spacial orthogonal coordinates depending on the chosen reflection plane, that can be modified by using a Dove prism.

Separable cases

State (16) can be (partially) separable in several ways. We first discuss the case where sum and difference coordinates can be separated but spatial coordinates canont (as in (1) of the main text). The two photon two dimensional wave function is given by:

In this case, in Eq. (14), we have that

with

and analogously for the  coordinate. The density matrix

coordinate. The density matrix  (

( ) is the trace over the r⊥± (

) is the trace over the r⊥± ( ) coordinate. We see that in the case discussed in the main text, we obtained the same expression as (17). However, when the state is separable in the spatial coordinates as well, we obtain pure states in (18) instead of mixed ones. In this case, the quantum state can be written as

) coordinate. We see that in the case discussed in the main text, we obtained the same expression as (17). However, when the state is separable in the spatial coordinates as well, we obtain pure states in (18) instead of mixed ones. In this case, the quantum state can be written as

Finally, let's discuss the case where states are separable in the spatial coordinate but not in the + and − coordinates, i.e., they can be written in the form:

A particular case of this state is the one dimensional distribution, as for example, the frequency states considered in the example discussed in the main text. In this case, Eq. (17) still holds. However, its interpretation is different, since the density matrices  (

( ) are the trace over the

) are the trace over the  (r⊥±) coordinates.

(r⊥±) coordinates.

In conclusion, we the modification proposed in the HOM experiment leads to the Wigner function of biphoton state in different coordinates. These coordinates depend on the properties and correlations existing between + and − coordinates of the biphoton, as well as its spatial coordinates.

References

Bouwmeester, D. et al. Experimental quantum teleportation. Nature 390, 575 (1997).

Gisin, N. et al. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145 (2002).

Walther, P. et al. Experimental one-way quantum computing. Nature 434, 169 (2005).

Reim, K. F. et al. Single-Photon-Level Quantum Memory at Room Temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 053603 (2011).

Aspect, A., Grangier, P. & Roger, G. Experimental Realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: A New Violation of Bell's Inequalities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 91 (1982).

Weihs, G. et al. Violation of Bell's inequality under strict Einstein locality conditions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5039 (1998).

Simon, R. Peres-Horodecki Separability Criterion for Continuous Variable Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2726 (2000).

Duan, L. M. et al. Inseparability Criterion for Continuous Variable Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2722 (2000).

Sperling, J. & Vogel, W. Verifying continuous-variable entanglement in finite spaces. Phys. Rev. A 79, 052313 (2009).

Lee, J. & Nha, H. Entanglement distillation for continuous variables in a thermal environment: Effectiveness of a non-Gaussian operation. Phys. Rev. A 87, 032307 (2013).

Jeong, H., Kim, M. S. & Lee, J. Quantum-information processing for a coherent superposition state via a mixedentangled coherent channel. Phys. Rev. A 64, 052308 (2001).

Toscano, F. et al. Sub-Planck phase-space structures and Heisenberg-limited measurements. Phys. Rev. A 73, 023803 (2006).

Dechoum, K., Hahn, M. D., Vallejos, R. O. & Khoury, A. Z. Semiclassical Wigner distribution for a two-mode entangled state generated by an optical parametric oscillator. Phys. Rev. A 81, 043834 (2010).

Walborn, S. P. et al. Multimode Hong-Ou-Mandel Interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 143601 (2003).

Walborn, S. P., Monken, C. H., Pádua, S. & Souto Ribeiro, P. H. Spatial correlations in parametric down-conversion. Phys. Rep. 495, 87 (2010).

Mukamel, E., Banaszek, K., Walmsley, I. A. & Dorrer, C. Direct measurement of the spatial Wigner function with area-integrated detection. Opt. Lett. 28, 1317 (2003).

Smith, B. J., Killett, B., Raymer, M. G., Walmsley, I. A. & Banaszek, K. Measurement of the transverse spatial quantum state of light at the single-photon level. Opt. Lett. 30, 3365 (2005).

Wigner, E. P. On the Quantum Correction For Thermodynamic Equilibrium. Phys. Rev. 40, 749 (1932).

Hong, C. K., Ou, Z. Y., Mandel, L. Measurement of subpicosecond time intervals between two photons by interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 2044 (1987).

Tasca, D. et al. Continuous variable quantum computation with spatial degrees of freedom of photons. Phys. Rev. A 83, 052325 (2011).

Eckstein, A. & Silberhorn, C. Broadband frequency mode entanglement in waveguided parametric downconversion. Opt. Lett. 33, 1825 (2008).

Stobińska, M. & Wódkiewicz, K. Witnessing entanglement with second-order interference. Phys. Rev. A 71, 032304 (2005).

Ray, M. R. & van Enk, S. J. Verifying entanglement in the Hong-Ou-Mandel dip. Phys. Rev. A 83, 042318 (2011).

Di Lorenzo Pires, H., Florijn, H. C. B. & van Exter, M. P. Measurement of the Spiral Spectrum of Entangled Two-Photon States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 020505 (2010).

Law, C. K. & Eberly, J. H. Analysis and Interpretation of High Transverse Entanglement in Optical Parametric Down Conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 127903 (2004).

Schrödinger, E. Die gegenwrtige Situation in der Quantenmechanik. Naturwissenschaften 23, 807, 823, 844 (1935).

Buono, D. et al. Experimental analysis of decoherence in continuous-variable bipartite systems. Phys. Rev. A 86, 042308 (2012).

Caillet, X. et al. Two-photon interference with a semiconductor integrated source at room temperature. Opt. Express 18, 9967–9975 (2010).

Orieux, A. et al. Direct Bell States Generation on a III-V Semiconductor Chip at Room Temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 160502 (2013).

Preble, S. et al. Single photon adiabatic wavelength conversion. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 171110 (2012).

Liang, Y. & Beige, A. Generalized HongOuMandel experiments with bosons and fermions. New J. of Phys. 7, 155 (2005).

Bocquillon, E., Freulon, V., Berroir, J.-M., Degiovanni, P., Plaçais, B., Cavanna, A., Jin, Y. & Fève, G. Coherence and Indistinguishability of Single Electrons Emitted by Independent Sources. Science 339, 1054 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge A. Orieux and A. Mandilara for fruitful discussions. This work was partially financially supported by ANR/CNPq HIDE and CAPES/COFECUB 640/09. SPW and AZ thank the FAPERJ and the INCT-Informaçao Quântica for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.D. and P.M. contributed to all tasks. A.K., A.E., S.D. and T.C. contributed to the definition of the problem and critical discussions. S.P.W. contributed to the study of the experimental aspects of the manuscript and to the application of our results to spatial degrees of freedom. A.E., S.D. and A.Z.K. contributed to the experimental aspects of the manuscript and to the detailing of the Hong-Ou-Mandel experiment. All authors contributed to the revisions of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information: Direct measurement of the biphoton Wigner function through two-photon interference

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Douce, T., Eckstein, A., Walborn, S. et al. Direct measurement of the biphoton Wigner function through two-photon interference. Sci Rep 3, 3530 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03530

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03530

This article is cited by

-

Relativistic Wigner functions in transition metal dichalcogenides

Journal of Computational Electronics (2018)

-

Hong-Ou-Mandel Interference with a Single Atom

Scientific Reports (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.