Introduction

The complexity of factors that contribute to inequitable health outcomes for Māori people in Aotearoa New Zealand (Aotearoa) require equally complex, multifaceted, and urgent solutions (Health and Disability System Review, 2020). Māori-led solutions and Māori models of health and wellness are critical as identified in Whakamaua: Māori Health Action plan 2020-2025 (Ministry of Health, 2020); Waitangi Tribunal’s Hauora report (Wai2575) (2019); and under the health reforms through the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act (Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act, 2022). We recognise that there is a longstanding critical underrepresentation of Māori in health professions. Building and strengthening the capacity and capability of the Māori nursing workforce, is integral to improving access to culturally safe healthcare delivery and achieving equity (Chalmers, 2020).

This article describes our haerenga (journey) of developing and implementing a workforce strategy – Earn As You Learn (EAYL) - to support the career development of the Māori unregulated health workforce (kaimahi) into a nursing career via an enrolled nurse (EN) pathway (Adams et al., 2021). Enrolled nurse registration requires completion of an 18-month diploma at any one of eight institutions, part of Te Pūkenga – New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology. Enrolled nurses are regulated by the Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ) under the EN scope of practice contributing “to nursing assessments, care planning, implementation and evaluation of care for health consumers and/or families/whānau” (NCNZ, n.d.).

The EAYL workforce initiative is one of several implemented under the wider EN/Nurse Practitioner Workforce Programme (the Programme), funded through Te Whatu Ora from mid-2020 through to end 2024. The University of Auckland, in partnership with several health organisations and tertiary education institutes, are responding to, amongst other objectives, increasing the capacity of the EN workforce to deliver services in primary health care (PHC) settings that improve access, including to mental health and addiction services. Increasing Māori, and Pacific, in the nursing workforce is central to the Programme. The vision for a proposed apprenticeship pilot, now known as EAYL, grew from the experience and knowledge of senior Māori nurse leaders at Mahitahi Hauora Primary Health Entity (PHE). The challenges identified for strengthening the EN workforce included lack of understanding of the EN scope in the PHC sector; rural location of learners and providers; and lack of supporting infrastructure, such as a framework incorporating clear guidelines, policies, reporting lines, and supervision.

The EAYL initiative began earnestly in Te Tai Tokerau (Northland), with a strong partnership forming between the University of Auckland, Mahitahi Hauora PHE, NorthTec, and health providers across the rohe (region). Since then, EAYL has gained traction in Tamaki Makaurau (Auckland) where we have replicated core components (Table 1) learned through our work in Te Tai Tokerau. This has involved intentional selection and prioritising of Māori health providers, resulting in shared investment from iwi providers, demonstrating their commitment to ‘growing their own’ Māori nursing workforce. This article describes the implementation, early outcomes, and salient learnings in the form of a model of the ongoing initiative.

Background

Throughout nursing history in Aotearoa, patterns of behaviour and attitudes towards Māori nurses, that actively depict marginalisation, discrimination, and racism, continue to be covert (and at times overt), sophisticated, and institutional (Hunter & Cook, 2020; Wiapo & Clark, 2022). Since the early 1900s, schemes to promote Māori to enter nursing have often failed because of colonial attitudes and westernised educational and health systems (Wilson et al., 2022). In addition to these traumas experienced by Māori ENs, for the whole professional group of ENs there is a history of hurt and distress related to changes imposed to their education, regulation, and scope of practice (Davies, 2020). Enrolled nursing has been nothing short of a roller-coaster experience from mid-twentieth century to the present.

The ‘Enrolled Nurse’ title was introduced under the Nurses Act (1977), having been through several previous iterations, including the ‘Registered Community Nurse’ (1965-1977), which required an 18-month training programme delivered by local hospital boards. In 1990 a review of enrolled nursing by the Department of Health (1990) raised concerns that the then 12-month hospital-based training manufactured a ‘limited qualification’ with a narrow scope. This resulted in the training being scrapped by NCNZ in 1993 (Davies, 2020). Over the next eight years the New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO) maintained a focused effort to reinstate enrolled nursing, with NZNO’s Māori Rūnanga (tribal council) arguing that enrolled nursing gave Māori the opportunity to enter the nursing workforce and to work with Māori communities to improve healthcare access (Meek, 2010). At the same time the Māori Council of Nurses raised issues of workforce equity, with concerns that Māori were being channelled into enrolled nursing, rather than registered nursing, because “they are so good with their hands” (Meek, 2010, p. 31).

After much pressure, in 2002 EN training re-commenced at Northland Polytechnic. Challenges have, however, continued. For example, in 2004, NCNZ dealt a further blow to those ENs who had registered since the 2002 training through a change to their scope of practice, published in the New Zealand Gazette (2004).[1] Overnight, 137 EN graduates became deregistered and re-categorised under a new scope of ‘nurse assistant’ (Davies, 2020). They were later reinstated as ENs following a motion tabled by David Cunliffe, the Minister of Health, in 2008 (New Zealand Government, 2008). In 2010, NCNZ were required to again change tack, announcing that ENs could be trained from 2011 under a New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) Level 5, 18-month diploma programme, delivered by Institutes of Technology or Polytechnics.

There continues to be concern around directing Māori into enrolled nursing, rather than registered nursing, causing workforce inequity (Wilson et al., 2022). Despite ongoing rhetoric, over the past two decades the percentage of Māori nurses has remained static at 8% of the total nursing workforce and underrepresented when compared to Māori being 17.4% of the national population (Chalmers, 2020; StatsNZ, 2022; Wilson et al., 2022). There is a need to increase the representation of Māori across the whole nursing workforce.

While the representation of Māori in regulated nursing scopes of practice is low, in the unregulated health workforce, 21% identified as Māori in 2017 (Sewell, 2017). Māori are less likely to work in skilled or professional occupations (Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment, 2022) and of all Māori in the health workforce, 71% are unregulated health workers (Sewell, 2017). The recent pandemic saw an increase in Māori kaimahi employed to support the COVID-19 response. This ‘surge workforce,’ provides a significant opportunity to support kaimahi into a regulated health profession, aligning with the Māori Employment Action Plan to give “kaimahi Māori lifelong opportunities to upskill, learn and develop” (MBIE, 2022, p. 3). Kaimahi work, live, and play in some of the most underserved communities, where they already have strong whanaungatanga (kinship connections) and understand the community’s historical dynamics, philosophies of care, challenges, and strengths (Crampton & Baxter, 2018). Supporting Māori to become regulated professionals to work within their communities, will increase the capability and capacity of a nursing workforce to provide culturally safe care (Hunter, 2019) and deliver on the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act (Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act, 2022) to promote both equity of workforce and health.

The initiative

The EAYL initiative is one approach explicitly for Māori (and increasingly Pacific) kaimahi already employed by health providers delivering services to priority populations. The authors have all been significantly involved in the development and/or implementation of EAYL. To refine and affirm our kaupapa (described later) a series of co-design workshops were held across Te Tai Tokerau in 2021 and 2022 by the Programme’s regional coordinator (CW) to explore with health providers and kaimahi their moemoeā (aspirations), barriers, and solutions to support kaimahi to become ENs. The kanohi ki te kanohi (face-to-face) co-design workshops were co-delivered by Māori and tauiwi and tikanga processes (Māori values and beliefs) were followed. This included karakia (a blessing to establish a safe protected space), whakawhanaungatanga (to support positive and collaborative connections and relationships) and sharing kai (food; to show hospitality and respect). The outcome of these co-design workshops was a discovery of longheld moemoeā by kaimahi to become nurses, and a framework of what is required to successfully support kaimahi to become registered ENs in their community.

Fundamentals for success included funding to reduce financial stress; academic development and support; cohorting students for collective progression; and support from their whānau and health providers. The workshops also consolidated investment and commitment by kaimahi to their hapori (community), which were often rural, in low socio-economic areas with high-priority populations, and the willingness of nurse leaders and the health provider organisations to support their success. One senior Māori nurse reflected, “When I can’t be there to care for my whānau, I want to know that another Māori nurse will be.” An email from a chief executive officer (CEO) of a rural Māori provider highlighted the value of this opportunity for kaimahi, health providers, and the contribution to whānau and hapori:

The kaimahi who have been given this opportunity still cannot believe this is happening, as it has been a lifelong dream for them to attend university. The qualifications will not only add to their personal and professional development kete [basket], but this is a sustainable method for rural hauora [health and wellbeing] organisations to retain their Māori health workforce. More-over [the kaimahi will] contribute to the overall vision of improving hauora outcomes for whānau Māori in Ngāpuhi me te [and] Aotearoa.

Before presenting “how” we implemented the initiative, we have briefly summarised the key components and stages (Table 1). The table is presented in its reductionist mode – simplified and linear. The reality is, as always, less straightforward. However, our learnings, through working with kaimahi, health providers, and educational leaders from institutes that deliver EN programmes (now part of Te Pūkenga) have led us to identify these key stages. What is absent in this table is the acknowledgement of the work undertaken by all involved to formulate an implementation plan that meets and honours the needs of each kaimahi and health provider and fulfils the kaupapa of the Programme. Throughout, we have endeavoured to uphold the values of tika (trust), pono (honesty) and aroha (love). Acknowledging the mamae (hurt) ENs, particularly Māori ENs have experienced historically, allows us to adopt a forward-thinking strengths-based approach to reshape and reimagine the future of Māori ENs.

The Programme Kaupapa (the vision and approach)

Our Kaupapa, or vision, was to increase the number of Māori ENs in PHC to deliver culturally safe care and improve health outcomes; build the capacity and capability of the Māori regulated nursing workforce; and improve hauora for whānau and communities by establishing EN models of care to improve access to mental health and addiction care and services. Purposefully, the initiative supports achieving optimal hauora and pae ora (healthy futures) for individuals (the emerging ENs), whānau, and hapori.

Kaupapa Māori principles and ideas formed our foundation for action. A kaupapa Māori approach seeks to understand and represent Māori, as Māori, and hold the position that to be Māori is normal and taken for granted. Te reo Māori (the Māori language), mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge), tikanga Māori (Māori custom), and ahuatanga Māori (Māori characteristics) were actively legitimated and validated (Cram, 2017). This approach also shifted discourse towards a strengths-based framework, focusing on Māori self-determination and validating mātauranga Māori (Oetzel et al., 2021).

Kaupapa Māori was integral to keeping the vision of developing and strengthening a Māori workforce as a key component of the overall EN/NP Workforce Programme. Workforce statistics, highlighting the significant number of Māori in the unregulated workforce (Sewell, 2017) and low representation of Māori in the regulated nursing workforce (Chalmers, 2020), evidenced the inequities relating to the status and (perceived) competence of Māori (L. T. Smith, 2021). The Programme sought to shift the status quo and the historical injustices entrenched in the history of Māori nursing development. This meant Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles and Te Ao Māori (Māori worldview) intentionally guided and provided an anti-colonial and anti-racist platform for all actions throughout the Programme (Cram, 2017).

Ethics

The article here reports on the development and implementation of the EAYL workforce initiative, and as such did not require ethics. However, the EAYL is being fully evaluated with ethics approval through Auckland Health Research Ethics Committee (AH25268).

Implementation and Early Outcomes

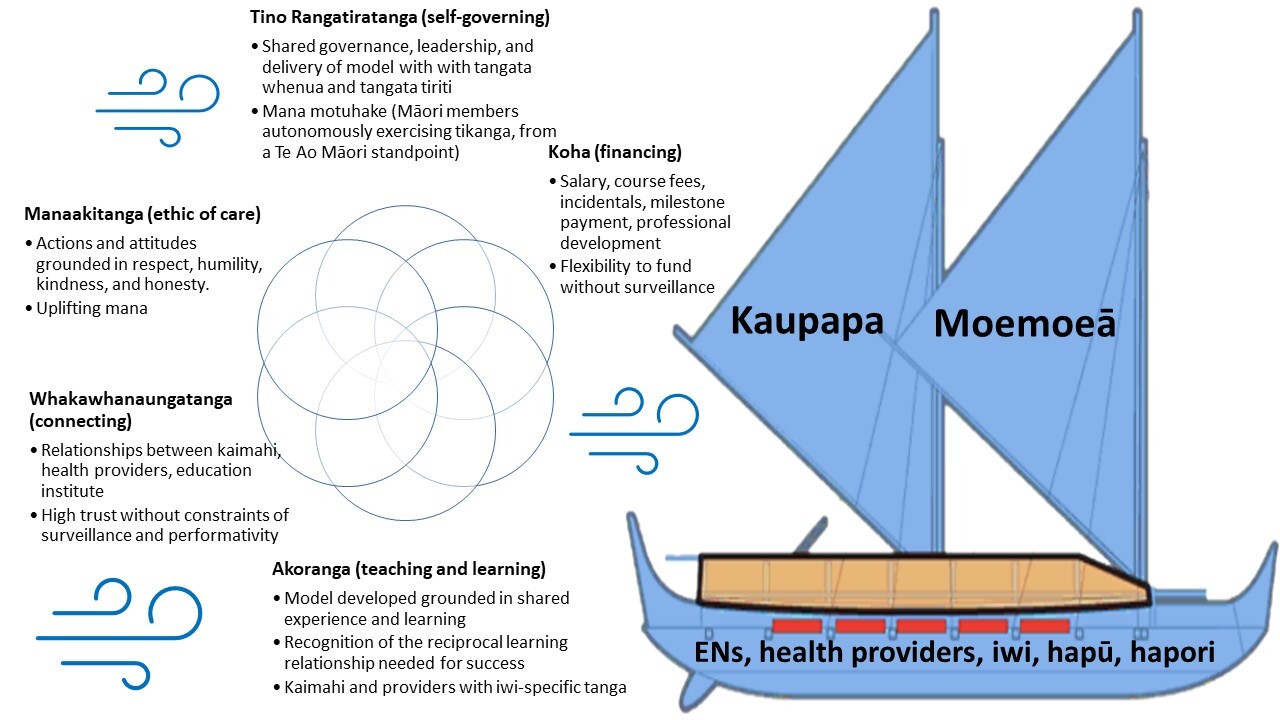

Establishing the kaupapa and conducting co-design workshops, led to the development of an implementation framework based on ongoing kōrero (discussion and reflection). Te Ao Māori principles and values, including tino rangatiratanga, whakawhanaungatanga, manaakitanga, koha, and akoranga were all integral in propelling the initiative forward to support kaimahi to become ENs (Figure 1). These principles and values are described below.

Tino rangatiratanga

Tino rangatiratanga is the principle of self-determination where Māori have autonomy and control, in our case, over the EAYL initiative. The EN/NP Workforce Programme governance is a Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership model with Māori (JD) and tauiwi (SA) as co-leaders. The governance group includes representatives from various educational institutions, health provider organisations, and professional organisations and equally represents Māori. Tino rangatiratanga through strengths-based kōrero was also essential to address mistrust from health providers and communities who have historically struggled with the relationship between themselves, the funders of healthcare, and tertiary education. While we worked closely with the health providers and kaimahi to ensure they felt empowered through the process, we found it challenging to navigate the provider-employee (kaimahi) relationship to ensure mana motuhake (self-determination) was maintained for all.

Whakawhanaungatanga

Whakawhanaungatanga is a social process used to support the initiative and the required relationships by sharing experiences and developing trust and accountability among those involved. Central to the success of the initiative was how the regional coordinator (CW) of the workforce team met kanohi ki te kanohi with health providers, kaimahi, the educational institute (of the EN diploma), and Programme co-leaders to ensure the initiative met the needs of the kaimahi, while aligning with the needs of each stakeholder.

Particularly valuable for the kaimahi, who have been mostly wāhine (women), was CW sharing the story of her academic haerenga as a mature Māori nursing student, impacted by competing social, cultural, and economic demands. Shared experiences collectively contributed to strengths-based solutions to challenges that kaimahi might also navigate. Another important aspect was how relationships were strengthened between the regional coordinator, NorthTec’s EN programme coordinator (BC), health providers, and potential placements. This relationship supports a seamless transition for EN students, through placements and into employment opportunities in PHC. Visibility of EN students also meant health providers offered student placements and the EN programme coordinator provided an improved understanding of the EN scope of practice. The relationship between the EN programme coordinator and the provider, also meant they were able to ensure that the student would be a good fit for the organisation and vice versa. The importance of this work and time cannot be underestimated. Whakawhanaungatanga built trust, solidarity, and collective accountability between the kaimahi, health providers, academic institutes, and the workforce team.

Manaakitanga

Manaakitanga is interpreted as showing respect, kindness, being, and bestowing hospitality (Pere, 1994). Limited resources within the workforce team and health provider sometimes made it challenging to strengthen manaakitanga by ensuring a supported transition from kaimahi to EN. To streamline manaakitanga, a clear pathway of responsibilities was developed and supported by ongoing kanohi ki te kanohi meetings. The initiative was also deliberate about interactions that upheld the mana of all involved. The regional coordinator’s close engagement with the providers and kaimahi supported and maintained the kaupapa. For example, some providers expected that they would bond kaimahi, where kaimahi would have to continue to work for the provider after registration as an EN. Kaimahi were reluctant to commit to this bonding and given they were being released from their place of work to attend their EN studies, this was not a reasonable expectation. Ongoing kōrero enabled the providers to instead create an environment where kaimahi would choose to remain as ENs. Guaranteed employment by the health provider post-registration supported an ethic of reciprocal respect, honesty, and generosity between stakeholders and the communities they intended to serve. Some providers even went beyond by supplementing funding as a sustainable investment in growing their Māori workforce.

Koha

During Māori ceremonial gatherings, the koha (gifting) protocol demonstrates the importance of sharing to build trust, generosity, and reflect mana in those relationships (Pere, 1994). For the initiative, funding (outlined in Table 1) was the practical expression of such koha, which consolidated the kaupapa and provided tangible evidence of the aroha required for success. The salary contribution was integral in the success of the EAYL model, affording kaimahi the opportunity to study. Kaimahi reported that without the funding it would not have been feasible for them to enter the EN diploma. One said to CW:

Without this support I would not be in a nursing pathway and would still be working as a receptionist.

The generosity, flexibility, and early availability of the funding respected the value of developing this workforce. The milestone payments provided recognition of the commitment demonstrated by the kaimahi and their whānau. Koha also created a visionary platform for providers when considering how an EN might address gaps in services within the community. For example, a Māori health provider with several kaimahi engaged in the EAYL initiative considered how ENs would provide school-based services. Another provider is using their koha to engage holistically with wāhine Māori that identify mental health and addiction issues as the result of domestic violence.

Akoranga

Teaching and learning in a reciprocal non-hierarchical relationship known as akoranga (Ministry of Education, 2018) also drove the initiative’s success. Our responsibility to learn and discover the potential of those involved was intentional through the co-design of the initiative, including the knowledge and experiences of the kaimahi, the tertiary education institute, the health provider, and other health workers. At the initiative’s core was building community capability and capacity to ensure the benefits of EAYL would reach and be responsive to whānau and hapori. This included the upskilling of the unregulated COVID-19 response workforce to become regulated ENs. Since the establishment of EAYL in Te Tai Tokerau, further opportunities to extend the EN workforce programme in other regions were also made possible based on our akoranga.

Early Outcomes

At the time of publication, there are 25 students active in the EAYL programme and one EN graduate. Of these 84% are Māori and 16% are Pacific. Fifteen of these students are based in Te Tai Tokerau. Before the Programme started just six ENs were working in PHC in Te Tai Tokerau. The first EAYL participant completed her EN training mid-2022 and has transitioned to work as an EN in her community, serving an enrolled population with 72% Māori, most living in Quintile 5 of the Deprivation Index. The EN is delivering a service with a holistic focus on young people’s wellness, with lifestyle assessments and early intervention for drug and alcohol use, anxiety, depression, and domestic violence.

Discussion

The EAYL initiative has to date, exceeded expectations to support the career development of Māori kaimahi into nursing careers through an EN pathway. Through the process of implementing EAYL, our findings suggest critical gaps exist within current workforce development models that are not responsive to meaningful equitable development of the Māori PHC nursing workforce (Wikaire et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2022). Our initiative’s early success demonstrates that a Te Ao Māori solution is integral to strengthening Māori representation in the health sector and has the potential to improve system responsiveness to priority populations, including for people living with mental health and addiction issues.

Cram (2010) observes that co-design using Kaupapa Māori supports change as there is compatibility with tikanga principles of whānau-centred well-being, focusing on positive experiences and future aspirations (moemoeā). Our initiative in Te Tai Tokerau covered a large geographical area. Travel and time were required to ensure whakawhanaungatanga established sufficient trust between the Programme coordinators, health providers, EN educators, and kaimahi to facilitate co-design. Feedback highlighted how the moemoeā of both Māori health providers and Māori EN students were impacted by multiple factors (competing social, cultural, and financial demands) that impeded their haerenga. Navigating this required a partnership approach to develop strategies, including the development of funding and support structures (educational, cultural, and clinical), which were strategies previously recommended by Te Rau Matatini (2015). A commitment was required to shift from the status quo to transformative workforce development models, at an individual, provider (educational and health), and governance level.

The expectation of success at an individual level maintained the mana motuhake of kaimahi to redress inequities and promote generational hauora (Reid et al., 2019). Being Māori was instrumental in shaping culturally appropriate support (Komene et al., 2023). This included flexible work placements, responsive modes of learning, cohorting tuakana-teina (peer mentoring) support models, and various academic entry points (Oetzel et al., 2021; Wikaire et al., 2017). A benefit of supporting cultural identity meant a return investment in working with hapori bringing iwitanga (people-specific knowledge) to meet diverse and complex health needs (Sewell, 2017).

The EAYL supported health providers to adopt a strengths-based approach to the opportunity presented by the COVID-19 surge workforce to upskill those kaimahi already leading in this space and promoting health equity (Davis et al., 2021). The success of the model required considerable investment and resource by the health provider organisations, their managers, administrative staff, and nursing leaders. This included that kaimahi were released from their roles to attend the EN diploma training and receive the required support in a timely way. Service continuation was necessary during the kaimahi’s release time on the EN diploma, which required rostering and backfilling of their role, a task known to be difficult to achieve, particularly in rural areas. During clinical placements the nursing team were required to preceptor the EN student and support their integration both as a student and then as a registered EN into their team. Finally, health providers needed to plan how to develop a model of care delivered by the EN to meet local health needs and ensure the EN received appropriate support and professional development. As the initiative progressed, some health providers offered further funding and resource support (for example, by employing clinical educators) as they saw the sustainable value of “growing their own” EN workforce for their hapori (Reid et al., 2022).

Intentional education and funding opportunities for Māori kaimahi are one strategy to redress workforce inequities. To ensure true Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnerships are enacted requires structural barriers to equity to be addressed to begin to dismantle colonising systems embedded in institutional racism (Eggleton et al., 2022). This required us to approach funding agreements with providers in ways that at least began to acknowledge mātauranga Māori and the racism persistent in the administration of the public health sector (Came et al., 2018). Our funding approach, koha, used a high-trust model without constraints of surveillance and performativity and enabled flexibility and innovation outside the dominant business-as-usual contractual arrangements with PHC providers. Alleviating economic burdens included providing flexible funding for students and providers to spend where most cost-effective (Reid et al., 2022). Solutions were grounded in making positive health decisions for hapori now and future generations, allowing for genuine autonomy over processes, systems, and advancement.

The early success of shifting the model geographically into a metro environment (Tamaki Makaurau, Auckland, and Te Whanganui-a-tara, Wellington) highlights the transferability and adaptability this model offers to others (McLelland et al., 2021). For example, the model appears to offer considerable potential for Pacific kaimahi (with four Pacific EN students currently enrolled). Pacific communities were adversely affected by COVID-19 and kaimahi were recruited in considerable numbers particularly in Auckland (A. Smith et al., 2021). As with Māori nurses, Pacific nurses are significantly underrepresented when compared to the Pacific population and should be a priority for national workforce initiatives (A. Smith et al., 2021). As with Māori workforce initiatives, ensuring programmes are culturally safe is central.

The EAYL initiative is in its early stages. A full evaluation as part of a research study is planned over the following 18-24 months, which will include both health provider and EN feedback. This evaluation is likely to provide substantive evidence for health workforce policy that focuses on growing the domestic nursing workforce. Of considerable interest will be the longer-term outcomes delivered by the ENs in their communities, as well as their individual career progression. Exploring how tino rangatiratanga, whakawhanaungatanga, manaakitanga, koha, and akoranga and what ‘by Māori, for Māori, to benefit Māori’ genuinely achieves through the enaction of Te Tiriti and Te Ao Māori worldviews will add substantially to mātauranga Māori and indigenous knowledge practices. The EAYL model, we believe, is evidence of the transformative ability of developing a regulated nursing health workforce that is responsive to community needs.

Recommendations

The key recommendations arising through our learnings from this workforce initiative are:

-

Intentionally prioritise Māori by developing workforce strategies that redress historical grievances and acknowledge the inherent value that Māori nurses bring to improving health outcomes for whānau Māori;

-

Legitimise Te Ao Māori within a eurocentric-western paradigm of health delivery and nursing education, recognising that such workforce strategies require additional resource (personnel, funding, time, and travel) for all stakeholders to achieve success;

-

Ensure funding models and agreements are flexible, designed to support success, deliver equity, and promote socio-economic, intergenerational wellbeing;

-

Provide accessible and affordable pathways for Māori to enter a regulated nursing career and for ENs to seamlessly transition to registered nursing (and potentially to nurse practitioner);

-

Explore how the EAYL can be adapted for Pacific unregulated health workers and Pacific communities;

-

Empower Māori communities, whereby individuals, whānau, and hapori can exercise their authority to local solutions to improve their health and well-being through investment in their own workforce.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the courageous EN students and health providers for their trust in our Programme; to the Office of the Chief Nurse and Ministry of Health nursing advisors for support and guidance.

Funding

Te Whatu Ora: EN/NP Workforce Development Programme

Conflict of interest

The authors are all involved in the development and/or implementation of the EAYL Programme.

The New Zealand Gazette is the official newspaper of the Aotearoa New Zealand Government. It is an authoritative journal of constitutional record and contains official commercial and government notifications that are required by legislation to be published. All changes to nursing scopes of practise have to be published in the Gazette.