Abstract

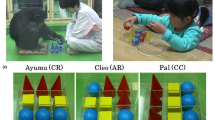

The stacking-block task has been used to assess cognitive development in both humans and chimpanzees. The present study reports three aspects of stacking behavior in chimpanzees: spontaneous development, acquisition process following training, and physical understanding assessed through a cylindrical-block task. Over 3 years of longitudinal observation of block manipulation, one of three infant chimpanzees spontaneously started to stack up cubic blocks at the age of 2 years and 7 months. The other two infants began stacking up blocks at 3 years and 1 month, although only after the introduction of training by a human tester who rewarded stacking behavior. Cylindrical blocks were then introduced to assess physical understanding in object–object combinations in three infant (aged 3–4) and three adult chimpanzees. The flat surfaces of cylinders are suitable for stacking, while the rounded surface is not. Block manipulation was described using sequential codes and analyzed focusing on failure, cause, and solution in the task. Three of the six subjects (one infant and two adults) stacked up cylindrical blocks efficiently: frequently changing the cylinders’ orientation without contacting the round side to other blocks. Rich experience in stacking cubes may facilitate subjects’ stacking of novel, cylindrical shapes from the beginning. The other three subjects were less efficient in stacking cylinders and used variable strategies to achieve the goal. Nevertheless, they began to learn the effective way of stacking over the course of testing, after about 15 sessions (75 trials).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Combinatory manipulation has been of interest to researchers as a prominent feature of object manipulation potentially shedding light on cognitive capability. Several terms have been used by different authors to describe the behavior of relating a detached object to another object or substrate: combinatory manipulation (Fragaszy and Adams-Curtis 1991), combinatorial manipulation (Westergaard 1993; Westergaard and Suomi 1994), secondary manipulation (Torigoe 1985), and orienting manipulation (Takeshita and Walraven 1996). The term “object–object combination” was used by Hayashi and Matsuzawa (2003) to refer to the behavior of combining multiple detached objects. Hayashi et al. (2006) reviewed the terms of object manipulation including combinatory manipulation.

References

Bayley N (1969) Bayley scales of infant development. The psychological Corporation, New York

Biro D, Inoue-Nakamura N, Tonooka R, Yamakoshi G, Sousa C, Matsuzawa T (2003) Cultural innovation and transmission of tool use in wild chimpanzees: evidence from field experiments. Anim Cogn 6:213–223

Case R (1985) Intellectual development: birth to adulthood. Academic Press, Orlando

Forman GE (1982) A search for the origins of equivalence concepts through a microanalysis of block play. In: Forman GE (ed) Action and thought: from sensorimotor schemes to symbolic operations. Academic Press, New York, pp 97–135

Fragaszy DM, Adams-Curtis LE (1991) Generative aspect of manipulation in tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). J Comp Psychol 105:387–397

Fujita K, Kuroshima H, Asai S (2003) How do tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) understand causality involved in tool use? J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Proces 29:233–242

Gibson EJ (1969) Principles of perceptual learning and development. Appleton Century Crofts, New York

Gómez JC (2004) Apes, monkeys, children, and the growth of mind. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp 83–93

Greenfield PM (1991) Language, tools, and brain: the ontogeny and phylogeny of hierarchically organized sequential behavior. Behav Brain Sci 14:531–595

Greenfield PM, Nelson K, Saltzman E (1972) The development of rulebound strategies for manipulating seriated cups: a parallel between action and grammar. Cogn Psychol 3:291–310

Hauser MD (1997) Artifactual kinds and functional design features: what a primate understands without language. Cognition 64:285–308

Hayashi M (2006) A new notation system of object manipulation in the nesting-cup task for chimpanzees and humans. Cortex (in print)

Hayashi M, Matsuzawa T (2003) Cognitive development in object manipulation by infant chimpanzees. Anim Cogn 6:225–233

Hayashi M, Takeshita H, Matsuzawa T (2006) Cognitive development in apes and humans assessed by object manipulation. In: Matsuzawa T, Tomonaga M, Tanaka M (eds) Cognitive development in chimpanzees. Springer-Verlag, Tokyo, pp 395–410

Hayes C (1951) The ape in our house. Harper, New York

Ikuzawa M (2000) Developmental diagnostic tests for children, 2nd edn. (in Japanese). Nakanishiya, Kyoto

Johnson-Pynn J, Fragaszy DM (2001) Do apes and monkeys rely upon conceptual reversibility? A review of studies using seriated nesting cups in children and nonhuman primates. Anim Cogn 4:315–324

Karmiloff-Smith A, Inhelder B (1975) If you want to get ahead, get a theory. Cognition 3:195–212

Köhler W (1957) The mentality of apes (translated from the second edition by Ella Winter). Penguin Books, Harmondsworth

Limongelli L, Boysen ST, Visalberghi E (1995) Comprehension of cause–effect relations in a tool-using task by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J Comp Psychol 109:18–26

Lockman JJ (2000) A perception–action perspectives on tool use development. Chil Dev 71:137–144

Mathieu M, Daudelin N, Dagenais Y, Décarie TG (1980) Piagetian causality in two house-reared chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Can J Psychol 34:179–186

Matsuzawa T (1987) Stacking blocks in chimpanzees (in Japanese with English summary). Primate Res 3:91–102

Matsuzawa T (2003) The Ai project: historical and ecological contexts. Anim Cogn 6:199–211

Matsuzawa T (2006) Sociocognitive development in chimpanzees: a synthesis of laboratory work and fieldwork. In: Matsuzawa T, Tomonaga M, Tanaka M (eds) Cognitive development in chimpanzees. Springer-Verlag, Tokyo, pp 3–33

Parker ST, Gibson KR (1977) Object manipulation, tool use and sensorimotor intelligence as feeding adaptations in cebus monkeys and great apes. J Hun Evol 6:623–641

Parker ST, McKinney ML (1999) Origins of intelligence: the evolution of cognitive development in monkeys, apes, and humans. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, pp 23–79

Potì P (2005) Chimpanzees’ constructional praxis (Pan paniscus, P. troglodytes). Primates 46:103–113

Potì P, Langer J (2001) Spontaneous spatial construction by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes, Pan paniscus). Dev Sci 4:474–484

Povinelli DJ (2000) Folk physics for apes: the chimpanzee's theory of how the world works. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Povinelli DJ, Dunphy-Lelii S (2001) Do chimpanzees seek explanations? Preliminary comparative investigations. Can J Exp Psychol 55:187–195

Reifel S, Greenfield PM (1982) Structural development in a symbolic medium: the representational use of block constructions. In: Forman GE (ed) Action and thought: from sensorimotor schemes to symbolic operations. Academic Press, New York, pp 203–233

Santos LR, Miller CT, Hauser MD (2003) Representing tools: how two non-human primate species distinguish between the functionally relevant and irrelevant features of a tool. Anim Cogn 6:269–281

Santos LR, Rosati A, Sproul C, Spaulding B, Hauser MD (2005) Means–means–end tool choice in cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus): finding the limits on primates’ knowledge of tools. Anim Cogn 8:236–246

Siegler RS, Chen Z (2002) Development of rules and strategies: balancing the old and the new. J Exp Psychol 81:446–457

Takeshita H (2001) Development of combinatory manipulation in chimpanzee infants (Pan troglodytes). Anim Cogn 4:335–345

Takeshita H, Walraven V (1996) A comparative study of the variety and complexity of object manipulation in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and bonobos (Pan paniscus). Primates 37:423–441

Tanaka M, Tanaka S (1982) Developmental diagnosis of human infants: from 7 to 18 months (in Japanese). Ootsuki, Tokyo

Tanaka M, Tanaka S (1984) Developmental diagnosis of human infants: from 18 to 36 months (in Japanese). Ootsuki, Tokyo

Torigoe T (1985) Comparison of object manipulation among 74 species of non-human primates. Primates 26:182–194

Uzgiris IC, Hunt JM (1975) Assessment in infancy: ordinal scales of psychological development. University of Illinois Press, Urbana

Vauclair J, Bard KA (1983) Development of manipulations with objects in ape and human infants. J Hum Evol 12:631–645

Visalberghi E, Fragaszy DM, Savage-Rumbaugh S (1995) Performance in a tool-using task by common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), bonobos (Pan paniscus), an orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), and capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). J Comp Psychol 109:52–60

Visalberghi E, Limongelli L (1994) Lack of comprehension of cause–effect relations in tool-using capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). J Comp Psychol 108:15–22

Weir AAS, Chappell J, Kacelnik A (2002) Shaping of hooks in New Caledonian crows. Science 297: 981

Westergaard GC (1993) Development of combinatorial manipulation in infant baboons (Papio cynocephalus anubis). J Comp Psychol 107:34–38

Westergaard GC, Suomi SJ (1994) Hierarchical complexity of combinatorial manipulation in capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Am J Primatol 32:171–176

Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew WC, Nishida T, Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin CEG, Wrangham RW, Boesch C (1999) Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature 399:682–685

Yamakoshi G (2004) Evolution of complex feeding techniques in primates: is this the origin of great ape intelligence? In: Russon AE, Begun DR (ed) The evolution of thought: evolutional origins of great ape intelligence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 140–171

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture in Japan (#12002009 and #16002001), from the biodiversity research of the 21COE (A14), and from JSPS core-to-core program, HOPE. Preparation of the manuscript was supported by Research Fellowship 16-1059 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists. Special thanks are due to Tetsuro Matsuzawa (who conducted the face-to-face tests with the subjects Ai and Akira, and sessions 1–10 with Ayumu) for supervision in the course of conducting experiments and manuscript preparation. I would also like to thank Masaki Tomonaga (who conducted sessions 1–7 with Cleo), Masayuki Tanaka (who tested Pan and conducted sessions 1–7 with Pal), Hideko Takeshita, and Masako Myowa-Yamakoshi for their support and helpful comments. I am grateful to Dora Biro for support given in the course of revising the manuscript. The daily running of experiments was supported by Sana Inoue, Etsuko Nogami, Laura Martinez, Yuu Mizuno, Tomoko Takashima, Tomoko Imura, Toyomi Matsuno, Shinya Yamamoto, and Tomomi Ochiai. Thanks are also due to Kiyonori Kumazaki, Norihiko Maeda, Shino Yamauchi, Juri Suzuki, and Akino Kato for the daily care of the chimpanzees. The present experiment complied with the laws of Japan, and housing and feeding conditions were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Primates produced by the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University (2nd ed., 2002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

Ayumu: first session

0P1/3P01/0U301/301T/-2L/0M/3P0/-1L/3CM/2U0/1P0/1K/0P10/-2L/0U3/0F/3U3/3P0/-1L/0,3,3M/1P0/-1L/3P0/3D30/3CD/0P1/-1L/0U1/0P0/2U00/1P00/3P100/-1L/1P100//

3P1/0U0/0U31/-1L/0F/3P0/1P0/3D30/3P10/-1L/3F/0P10/3P010/-1L/3P010//

0P0/3P00/-1L/1P00/3P100/3A/-1L/3P100/-1L/3P100/-1L/3CM/2U100/3P100/-1L/3P100/-3L/3P1/0U31/-1L/0U2/3F/0L/3P0/1P0/3D30/3P10/0P310/-2L/0P10/-1L/3P10/-1L/0U10/0M/0P10/3P010//

1U0/0,0,1M/0P3/0K/0U03/-1L/0P0/-1L/3P0/-1L/1P0/0P10/-2L/3M/3P0/-1L/3M/0P0/3P00/3U300/-2L/3P0/3U30/-1L/3P0/-1L/0U3/0P0/1U00/-1L/1P0/3P10/0U310/-2L/0U3/0,0,3M/3U1/0P0/3P00/2U300/3A/-1L/3CB/2U00/1P00/3P100//

0P0/1P00/3U100/-1L/2U00/1P00/3P100/-1L/3U100/3CC/1P100//

Pal: first session

3M/0B/2H0/2M/0P1/0P01/3T/0A/3T/0A/-2L/0U0/0U1/0F/1L/0P0/3T/0A/3CD/0D00/0P1/0P01/3T/0A/001T/-2L/1R/0P1/0P01/001T/-2L/1R/1H/0P1/0P01/001T/-2L/1M/3U0/3F/0P0/0D00/0F/3T/0P0/3T/0D00/0P0/0A/3H/3R/3U00/3CC/1P00/1A/3CB/3CM/1P100//

0P0/1P00/3U100/3M/1A/3CB/1P100//

1M/1CM/2U0/1P0/0P10/3U010/3CM/3CB/1P010/1A//

3T/0P1/3T/0D01/0P0/1P00/3CB/1P100/1A/1D1100/1M/3CB/2U100/1P100/1A//

1P0/3U10/3CB/1P10/0U110/0M/0CB/0P110/0A/-3L/0,3M/0P0/3CB/1P00/3M/3CB/1P100/

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashi, M. Stacking of blocks by chimpanzees: developmental processes and physical understanding. Anim Cogn 10, 89–103 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-006-0040-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-006-0040-9